Novellas

Novellas

“The Price of Two Blades” by Pete Butler

“Destroyer” by James Enge

“The Natural History of Calamity” by Robert J. Howe

Short Stories

“Dark of the Year” by Diana Sherman

“The Hangman’s Daughter” by Chris Braak

“The Bonestealer’s Mirror” by John C. Hocking

“The Word of Azrael” by Matthew David Surridge

“The Mist Beyond the Circle” by Martin Owton

“Freedling” by Mike Shultz

“The Renunciation of the Crimes of Gharad the Undying” by Alex Kreis

“Devil on the Wind” by Michael Jasper and Jay Lake

“The Girl Who Feared Lightning” by Dan Brodribb

“Red Hell” by Renee Stern

“The Lady’s Apprentice” by Jan Stirling

“The Wine-Dark Sea” by Isabel Pelech

“On a Pale Horse” by Sylvia Volk

“La Señora de Oro” by R. L. Roth

“Building Character” by Tom Sneem

“Folie and Null” by Douglas Empringham

Reviewed by Steve Fahnestalk

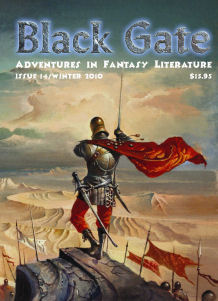

When I first opened the very thick envelope from Kansas City, I thought that Dave had messed up and sent me a Black Gate anthology instead of the magazine issue I expected. Full-color glossy perfect-bound wraparound cover on 380-plus pages containing not one, but three novellas, and sixteen stories. Plus poems, book and game review columns, letters, editorial and a comic strip—and handsomely illustrated throughout. I was poleaxed, banjaxed, gobsmacked and just plain overwhelmed.

For those of you who bewail the terminal illness of the publishing industry, the loss of the midlist, the paring down of the professional story market and the death of the illustrated magazine, ease up. I’ve seen more professional-quality short stories in the last month in my mailbox, half of them in this magazine, than I had in the previous six months—and that includes a trip to the library’s sf/f section. Professional-quality sf/f stories are alive and thriving—in the hands of the small presses!

Let’s jump into this with a look at the first novella. “The Price of Two Blades” by Pete Butler chronicles the life and times of a bard/storyteller, one Nikolai, who finds himself in a small village, Willowfeld, with a rather large graveyard: hundreds of graves with marble stones, lovingly maintained. Since stories are the bread-and-butter of entertainers, Nikolai could feel in his bones that this was a major story that would bring him fame and fortune. What could have transpired in this tiny town?

Nikolai theorizes that this might be the unknown place where King Kruthas, king of the bandits—who had ravaged the countryside for years, but disappeared suddenly—met his fate some twenty years ago. The storyteller who could tell that story would be set for life, possibly even finding a place at some court rather than having to roam from town to town to earn his supper. He sets about cozening the story from the reluctant villagers. Eventually, he gets them to tell him the story, but he must swear to learn the whole story before he can leave and share it—and he has no intention of spending even one more night in this village than he has to, because he knows how to flesh out a story and will soon be off to make his fortune.

He learns about the sorcerer, Wellin, who had lived anonymously in the village, but who revealed who he was when it became obvious that Kruthas intended to kill them all and ravage the village for daring to not pay his tribute. Wellin had told the villagers that he lived simply because he refused to pay the price to be a powerful sorcerer—but that he would pay that price to protect the others. That price was his life. But that was only the first payment; the villagers would have to pay the rest, and none of them knew how steep that price would be.

Eventually, Nikolai learns, a man called “Two Blades” comes to protect the village from King Kruthas and his bandits—and it is then the people of Willowfeld learn what they must pay to protect their homes and families. Nikolai also learns that he must pay part of this price to learn the story. Although there is no clear setting or period for this novella (other than the generic “middle-ages-kinda-fantasy”), you do actually get a sense of place from it—though if hard-pressed, you wouldn’t be able to say where or when it was. The people are not fully-fleshed, but that’s hard to do in a novella, and I wouldn’t say the story suffers overmuch from it. It’s not a great story, but I found it easy to read.

The second novella, “Destroyer,” by James Enge is, apparently, one of a continuing series of stories of Morlock Ambrosius, who is (according to the sidebar) a hunchbacked wizard. Or at least it says so in the review column; I haven’t read any others, so I’ll treat this as a stand-alone. (Are we allowed to say “hunchbacked” any more? Shouldn’t it be “bent-enabled” or something?) Thend is the protagonist of this story, and Morlock the apparent boyfriend of Thend’s mother, Naeli. Thend, his mother, Morlock and the rest of the family are fleeing some calamity from Sarkunden in the south towards a high pass in the northwest—they are attempting not to be seen by the insect-like Khroi and the Khroi’s enemies, the giant spiders, by staying between the territories of the two species.

Thend and Morlock come upon a Khroi, trussed up and hanging from a tree—awaiting his eventual fate as a meal for the spiders—and because Thend is young and passionate about doing the right thing, frees the Khroi, which will have consequences later. Later, they find the Khroi’s dragon (he was the rider) dead, and a werewolf near the corpse being menaced by a group of spiders and their leopard-snakes. Morlock and the rest help the werewolf escape, and the spiders flee.

Eventually, the Khroi and the dragons they ride (it is an association of free beings, not a master/slave relationship—a fact that Morlock takes advantage of later) capture the party, and the Khroi set about implanting their eggs in the captured humans.

How they escape, and how Morlock sets the dragons and the Khroi at each others’ throats, and how the werewolf and the Khroi Thend gave aid in the beginning, form the bulk of the story; we also learn how Thend becomes a seer and learns something about power and its costs as well. Like other stories in this issue, notably the Braak story, it’s also a story of personal growth for a young person. I liked it well enough that I’m going to search out Enge’s other stories about Morlock.

“The Natural History of Calamity” by Robert J. Howe is a novella written from the point of view of Debbie Colavito, a “karma detective” in New York City (yes, our NYC). It’s very rare to have a story written by a male from the female point of view; it’s even rarer for it to actually work. I never doubted for a minute that this was a female talking, but maybe that’s my ignorance as a male. Anyhow, I liked that part immediately.

Debbie is something unusual in New York: she can see karma imbalances, and if necessary, can give a little “nudge” to a person’s karma to help it balance. (Yeah, I know, it’s all crystal-sucking bulldookey, but bear with us for purposes of story, okay?) It seems that karma obeys the Second Law of Thermodynamics and wants to balance, and Debbie’s gift allows physics(?) to prevail.

So she gets hired by Will Charbonneau, a nice balanced guy, to find out why Becky Sandor, his girlfriend, dumped him for a used-car salesman. Well, a car salesman, anyhow… you know the type. They’ve never even had an argument, so Will needs to know if there was some sneaky underhanded karma-type thing happening that Debbie can undo with her gift to bring Becky back.

Debbie finds out that Mike, the salesman, is not only someone she knows, but a guy she knows and hates—he was her first sexual experience, and it was forced. You know, date rape. Girl says “no,” guy ignores it. So Debbie is positive that there has been hanky-panky—what girl would willingly give up a nice guy like Will for a sleazeball like Mike?

But there are twists and turns to every good story, and this one has more than its share… like, every time Debbie tries to do something to level Becky’s or Mike’s karma, her own suffers. But she can’t figure out why; and by the time she gets wise, it’s almost too late.

An original concept, as far as I know—and in some ways reminiscent of a feminine version of Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden, in execution. But on the other hand, a good, fun read—and again, written from the feminine viewpoint, which lifts it (IMHO) above many others. Recommended.

Short Stories

“Dark of the Year” by Diana Sherman is about Matai, a grandfather and vintner, who is trying to find a name for his infant granddaughter. Without a name (and it cannot be just any name; it must be her true name, which nobody knows) the child is vulnerable to the Shadows and their darkling subjects during Moondark—every year many children are taken by the Shadows to become yet more darklings. Matai is raising this child alone, and vows that she will not be taken. The story details his journey to find a dying man, perhaps a soldier, or a Darkmage, who will be able to speak the unknown name.

The milieu is standard fantasy; a vague sense of the Middle Ages or perhaps earlier—but Matai and the child, as well as the people they meet on this journey, are well delineated—and the reader gets caught up in this old man’s struggle to save his granddaughter. He does indeed find her name, but there’s a price to be paid for saving the child. Nicely written.

“The Hangman’s Daughter” by Chris Braak is about Cresy, a girl on the cusp of womanhood. Her father has come down in the world, and they’ve had to change continents; they now live in the squalid area of Shattertown, in Corsay in the southern hemisphere. Cresy has made new friends in the time they have lived in Corsay, and she liked to wrestle with Ally, Dorian and Denholm, until she showed she could beat them all (it was easy; after all, she was used to wrestling Therians, those ape-like creatures that share their world. And she can climb buildings and run across rooftops almost as if she were one of them.).

But Cresy has a problem. Night after night, she wakes from a dream of suffocating (as many children do)—but one particular night she thinks she saw something sitting on her chest and drawing the breath from her lungs. In these dreadful dreams she is paralyzed and can only wait for the dream to end so that she may draw a full breath again. Then, questioning the boys she plays with, she finds that all the children of Corsay have this problem. “Everyone gets those. It’s the bogeymen,” says Ally.

How Cresy finds her personal center and gains the strength to face her nightmares face on (and what she finds when she does) is the crux of the story. A nice little tale of personal growth set in a less-than-usual fantasy world. Cresy realizes (as I did when I was a preteen) that one must confront one’s bogeymen or be subject to them forever. (And “The Hangman’s Daughter,” though a somewhat hackneyed phrase, is apt here, and relevant to the story.)

“The Bonestealer’s Mirror” by John C. Hocking is a more traditional swords-and-sorcery tale, this one featuring Hocking’s continuing character Brand the Viking. Brand and his comrades, who owe fealty to Prince Asbjorn, have come to a small island to find out why Mord has lit a signal fire. The prince and his men are on the way home after rescuing the prince’s abducted sister, when they see the fire. Since Mord is a subject of Thorgeir Broadshield, Asbjorn’s father, they have stopped to see what the fire signifies.

What they find on the island is black sorcery and death—many of Mord’s men are dead from a demon-beast which takes bones from its victims; and now that the knarr has landed on the isle, that death is moving among Asbjorn’s men as well. Written by someone who obviously knows his Viking material well, and who has written at least one Conan novel, this story follows the best traditions of S&S—heavy-thewed barbarians, demon-haunted towers, flashing axe-blades and plunder. Who could ask for more?

“The Word of Azrael” by Matthew David Surridge is not so much a story as a shortcut version of an epic. Isrohim Vey meets the angel Azrael on a battlefield, and the angel speaks a word to him. Thereafter, Vey seeks to meet the angel again; in fact he dedicates his whole life to the quest. Armed with the Nameless Sword, Vey becomes the nearest thing to the Angel of Death himself over the years as he looks for the real Angel.

Although I liked the quest, and the various set-pieces therein, my problem is that it’s not so much a story as a teaser. Any one of the set-pieces could form a whole story (or even a novel)—but we’re rushed from one to the next with barely a pause for breath. I’d recommend this as reading material, but with reservations.

“The Mist Beyond the Circle” by Martin Owton is again set in the standard fantasy milieu, and all the characters thereof are generic peasants—except for one thing. Padraig, the narrator, and his friends Aron, Niall and Tomas have been out cutting turf (I’m assuming this is peat) and, on their way home in the evening, see and smell the smoke before they see their destroyed settlement. Most of their homes have been burned, and their cattle and families have (those who aren’t killed outright) been taken—presumably to be sold into slavery. The Earl’s castle is two days away on foot, and before they could get there and back, the raiders and their captives would be long gone.

But Aron has a secret—he hid a cache of Army swords under the midden heap in case of extremity—and now the group has to chase the raiders and retrieve their lost people and cattle. Fortunately, the villagers can cut across country and are not hindered by having to round up and keep track of captives, so they feel there’s a good chance of retrieval. And Aron knows a way to bring out any hidden gifts (the Sight) in the villagers so they can track their loved ones.

But the way there leads through a field with barrows, and one of the barrows has a guardian, a thing of mist and magic that cannot be fought with swords. Competently written, and if there’s nothing really new here, so what? It’s a good read on its own, although you probably won’t see it in any “best of” anthologies.

“Freedling” by Mike Shultz is about Naia, the titular “freedling”— who is an artisan, carving pleasing designs into pillars in the tower of Cer Vassir, a “sorcer” or mage. One day she is finishing a pillar, when quite literally, the roof fell in on them. As she is about to escape the collapsing tower she is held back by Vassir, and a piece of rubble knocks her unconscious. When she awakes, she finds herself trapped in a small portion of the central area of the tower with the dying sorcer.

The rest of the story details Naia’s attempts to escape not only the tower but the sorcer, who knows he’s dying and wants to take her body as his own. Cleverly written—and like “The Hangman’s Daughter,” a tale of personal growth.

“The Renunciation of the Crimes of Gharad the Undying” by Alex Kreis is a somewhat sly recounting (on paper, by the hand of that self-same Gharad) of all the crimes of an immortal tyrant who’s been overthrown by the populace of Falland, aided by his once-chief general. And something of an apology to the people he oppressed for so long; complete with descriptions of what his most faithful followers might gain from being his faithful followers, as well as where to find the powerful Orb that gave him magical powers—and a description of exactly where he’s being held captive forever. The wise reader can figure this one out easily.

“Devil on the Wind” by Michael Jasper and Jay Lake is not a pleasant story about happy peasants living in a Renaissance Faire kind of la-de-da medieval world; it’s a tale of blood, pain, magic and the costs of being powerful. Lena is one of the Redeviled, a Killaster witch in the land’s most powerful eight-of-power.

Lena has just undergone her fifth suicide—a method by which the Redeviled gain more power. The Killaster Witches, led by Black Mattieu, have just received what should have been tribute from one of the lords, Prince Falloe of Ironkeep. Yet instead of the expected oath-price, what the prince had sent were two copper coins—a major insult, and one which will not be allowed to pass unnoticed. Aided by Rego, whom she despises and has every intention of killing slowly when time permits, Lena is sent to show the prince the error of his ways.

In time she and Rego confront the prince, who seems to have found a source of power of his own, and Lena learns and teaches a few lessons about alliances and treachery. And we learn why the Redeviled are called that.

This is one of my favorite stories of the issue, not because I like the milieu created by the two authors—the protagonists live for power and power alone—all other pleasures in their lives are secondary, like sex, food, drink—and they call us ordinary folk the “soon-dead” and the things they do to each other and others are pretty shameful and disgusting; nor am I fond of any of the characters, Lena included. What I do like about this story is that Lake and Jasper are two of the very few fantasy writers who seem to understand that power demands a price. She and her fellow wizards pay a price with their very flesh and blood, pain and sacrifice.

So many fantasy stories have wizards who can just wave their wands and do just about anything without any problem, ignoring things like physics, personal pain and fatigue, and so on. In this story we see that in order to affect the real world, real sacrifice has to happen. And I like that. (You will note that there appears to be a theme in this issue about payment for power. This one is just more graphic than most.)

“The Girl Who Feared Lightning” by Dan Brodribb is a modern urban fantasy involving a security guard in a company town, who is not happy working for a corporation that attempts to sweep all unpleasantness under the rug. Cara has discovered a body stuffed into a culvert (a body missing its heart, watch and shoes), and the Avalon company spokesman won’t let her call it in to the police. Later, Cara wonders what it is about the security guard uniform that leads people like that to assume you’re stupid. She’s not stupid, and she’s not afraid—even though she finds out that there’s a mummy missing from a sarcophagus in one of the company labs. Okay, missing might not be right—“escaped” is the word the company spokesman uses.

Although Cara might be afraid of lightning, and spiders and some other stuff, she’s definitely not worried about mummies—so when she finds the company man hanging trussed up with his head down, being menaced by the Nameless One (from the era of Amenhotep II) with a knife, she jumps in. “Put the knife down,” she tells the mummy. “No thanks,” he says. “That’s what got me entombed in the first place.”

Cara eventually triumphs over the mummy, the company and all—but needs to look for another job, as some valuable company property (the aforementioned mummy) got, er… damaged… in the process of saving the company guy, and the company wants Cara to pay them back. Cute, and well written.

“Red Hell” by Renee Stern could be, with very few modifications, an alternate-world science fiction story instead of fantasy. It’s so well written, however, that it works either way; we have a mining town bounded by impassible mountains, where involuntary servitude is the rule rather than the exception, and the only way in or out is by dirigible-equivalents—does it matter whether the dirigibles are gas bags or wooden containers full of magic, whether the indentured are kept in by magic tattoos or electronic ankle bracelets?

Kellen is press-ganged into Red Hill (called “Red Hell” by the natives) and marked with a fake indenture tattoo—fake or not, it has the same magic marking as a real one—and forced to work off his indenture with whatever day labor he can get; his fellow indentures, Tully, Too-Tall and Preacher, are in the same boat—but Kellen gets hired for a day of heavy sewer cleaning (scut work) by Soiberon. Despite his gnawing hunger, Kellen works hard to fulfill the contract—only to have Soiberon accuse him of theft at the end of the day rather than pay him. Soiberon allows Kellen to “coerce” him into giving Kellen a magic ring that will hide his indenture tattoo; Kellen thinks this will help him escape from Red Hell by helping him hide in the hold of one of the airships.

During that attempted escape, Kellen learns that not all magic is what it’s cracked up to be, and that desperate people you work with are not necessarily your friends. Kellen finally finds a way out of Red Hell, but he, too, must pay a price—but that price has nothing to do with his own self-respect. I liked this story a lot!

“The Lady’s Apprentice” by Jan Stirling is about Nyla, an old woman who once was a rich, powerful sorceress—so much so that for the sin of pride, she was banished to a hut on the edge of the forest and stripped of wealth and power—both physical and magical—by the titular Lady, who appears to be somewhat of a goddess. The Lady is given to calling on her “apprentice” (more of an indentureship, if you ask me) to do things for her—answer people’s prayers by direct intercession—at odd hours of the day or night.

In this case, a young couple has had their baby stolen by a Dark Mage who wants to use it as a sacrifice to summon a demon. This, the Lady views as a no-no, so she sends Nyla to take care of it, also granting her the return of her powers to help her accomplish this task. Although she does so, and in quite a clever fashion, it would appear that Nyla still hasn’t learned the lesson for which she has been “apprenticed.” The Lady herself appears to Nyla—not to chastise her, but to remind her why she is doing these things. Nyla hasn’t yet taken the lessons to heart—that the price here, of pride, is power. A slight story, but well written. (And I might remind Jan Stirling that the mage might not be chanting “foetid” words, as “foetid” (or fetid) means smelly, basically.)

“The Wine-Dark Sea” by Isabel Pelech concerns Newyn, a for-hire assassin from Altirn, visiting a sea-side village for no stated reason, except she is traveling with “The world’s Least-helpful Burro” on her way to a job, probably. Newyn’s wrappings betray her profession; she’s wrapped up like out traditional mummy, with ne’er an inch of skin showing. In addition, she wears a mask, because her face is disfigured from a childhood encounter with wild “lohan” magic. (An unfortunate name. In our world Lohan magic is going to jail, and rightly so!)

Two women seek her out and hire her to rescue the son of one of them from a near-sunken city in the sea nearby. It’s the kind of thing Newyn is good at; she is a city person and is familiar besides with lohan-taint, which appears as a mist–but as her face can attest, it’s a mist you don’t ever want to touch. The city has a strange property–even under water, you can breathe there.

During Newyn’s travels to and in this sunken place, she encounters revenants and visions of her younger self–all products of lohan-mist and all seeking to drag her down and destroy her. But Newyn has experience with the mists, as all assassins must, and will not easily succumb, though the mists know her deepest secrets and taunt her with them.

Eventually, Newyn rescues the young man, though he is tainted by his brush with the mist, and may remain simple the rest of his days. Although we and she have learned why she does what she does–the lesson came in the mist–the people who employ Newyn do not and cannot know. Well written.

“On a Pale Horse” by Sylvia Volk is a departure from all this traditional fantasy—it is an Arabian fantasy about a young Bedouin (“Bedu”) woman named Salsabil (after a fountain in Paradise)—who is in charge of a horse by the same name. She calls the horse “sister”—and Salsabil the horse is allowed to sleep in the women’s tent, as she is a special mare, much treasured (like Salsabil the girl) by Ibrahim, the patriarch.

One day, not long before Salsabil the horse is to be bred, and Salsabil the girl is to marry her cousin, Mosa, she (the girl) comes to her father and tells him of a white stallion that has been courting the mare; a stallion that is perfect in every respect save one—it has a horn on its forehead. It is then that Ibrahim knows his daughter is mad. But before he can do anything about it, the raiders from the north attack the family for their water rights, for the summer has been bad and water holes have dried up all over the desert.

Volk has packed this story with information, without ever once putting in an expository lump that I could see; in the course of it one learns (if one did not already know) a ton about Bedouin customs, mores, habits and so on—and yet managed to make the somewhat hackneyed plot about a virgin and a unicorn come to fresh life. And here is no vague middle-ages fantasy world, but a well-realized Arabian analogue full of characters one can understand and empathize with, and also full of action and adventure. A nice change from the usual.

“La Señora de Oro” by R. L. Roth is about gold mining in California in the mid-nineteenth century. The titular señora is not only made of gold (she’s a little figurine that hangs around a miner’s neck) but she is somehow linked to gold. The narrator, Tom, has left his hardscrabble farming life to seek his family’s fortune in the gold fields near “Marapoza” (Mariposa), accompanied by his friends Henry and George. But gold mining is as hard as farming and pays just about as well. In a series of letters to his family back home, Tom tells them how Henry catches the cholera and dies, but Tom and his new partners André and Pierre, are starting a “Long Tom” to process more dirt, something a lone pair of miners can’t do well. (A Long Tom runs dirt and water down a long ridged trough, where the gold lies in the bottom and the dirt washes out.) They’ve also taken on Hector and Juan to help with the mining, but they’re not doing too well.

Until one night when they come upon an old man lying on the ground with two sacks of gold; and when he dies, they find around his neck something that Juan (“Hwan”—Tom’s not the world’s best letter writer in English, let alone Spanish) calls “Saynoda dayodo” (Señora de Oro), which they find out can lead them to the best placer spots.

But lest we forget, California miners fell victim to something we call “gold fever”—and those who depend on Saynoda catch a particularly pernicious version of it—they’re never satisfied and need more and more. You can read the ending yourself to find out what becomes of Tom and his partners. Again, a departure from the standard fantasy tropes one sees over and over.

“Building Character” by Tom Sneem concerns the age-old conflict between story and character. Or, in this case, author and character. The character is the viewpoint character in this story, who is subject to the whims and purple prose of an author he refers to as The Kid. (At one point, when the female character’s cup size increases by three sizes, the character muses, “What is this guy? 13 years old?”)

Eventually, the two (author and character, not character and female character) come to some kind of rapprochement, and the story is resolved… no, the beginning is resolved to the character’s satisfaction. Cute, but not wholly original in concept. And is “lithesome” really the best version of “lissome”?

“Folie and Null” by Douglas Empringham concerns one Rhing, wanderer and involuntary man of leisure, having no real trade to fall back on. Rhing does have, however, a magic charm that enlarges into a real sword in case of danger, which he got by slaying a dragon.

At a bend in a road, Rhing comes upon a caravan with a slain adept lying nearby (judging from his robes); at first Rhing is tempted to search the caravan, but he sees bedding and the like strewn about the area and judges that the bandits or killers have beaten him to it. He does, however, find a strange ball lying in a puddle, and pockets it.

Later, in a tavern’s stables, Rhing discovers that the ball was actually the adept’s apprentice, who names himself Folie, and the two decide to travel together. They run afoul of a disgraced nobleman and his sister, who have fallen on hard times; later, they are forced to fight the two.

Meanwhile, Rhing has, accidentally (a la Bilbo Baggins), found a “null ring” which figures in the story as well as the title. My guess is that we’ll be seeing more of this odd couple (Folie and Rhing) in future stories. While a slight piece, it reads well and is not boring (my cardinal sin for fiction).

So overall, my impression of this magazine was so favorable, that my wife and I are going to subscribe to it (paper subscription)—I can’t wait to see what the editors have in store for us! My copy of #14 is very well thumbed indeed, as I read and reread these stories. I predict you’ll have a good time with it too.

Black Gate‘s website can be found here.