Tangent Online Presents:

An Interview with James P. Hogan

(June 27, 1941-July 12, 2010)

Interviewer:

Dave Truesdale

Location:

Kansas City, Missouri

Event & Date:

ConQuest 24

May 28-30, 1993

Interview originally appeared in Tangent No. 1, July/August 1993, and is reprinted here for the first time.

Below is an interview with James P. Hogan exactly as it appeared (including the original introduction) in the first issue of the second incarnation of Tangent (the original Tangent having a run from February 1975 through Summer 1977).

The only item original to this interview is a recollection I share now. When Jim and I entered his hotel room to do the interview and he offered to share his nearly full bottle of Bushmills Black Bush Irish Whiskey, I asked if I could smoke. He nonchalantly answered with a wave of his arm and said, “Go ahead. Set yourself on fire for all I care.” Momentarily taken aback (but realizing this must just be Jim’s libertarian side showing up–I hoped), I knew that if I was going to be drinking whiskey during the interview I had to smoke. So I did. It didn’t seem to bother Jim at all, as you will see. I also remember thinking that he looked like the embodiment of a giant elf. He’d get this certain grin on his face, and if he was looking in your direction his ears stuck out just so, and he looked for all the world like a grownup version of the proverbial Irish leprechaun. You couldn’t help but return his grin. Throughout the interview as I sat at the room’s only table with the tape recorder running, drinking whiskey and smoking, Jim would pace back and forth across the room answering questions at length and sipping generously from his own bottomless glass of whiskey. Full of energy, he never took a seat. And we almost finished his bottle of Bushmills Black Bush. Terrific stuff that.

Original Introduction

James P. Hogan was born in London in 1941. He now lives in Ireland but spends extensive time in the U. S. It was my great pleasure to speak with him at ConQuest 24, May 28-30th in Kansas City, Missouri. He proved to be an interviewer’s dream; he likes to talk and definitely has something to say. The first thing to happen once we sat ourselves down in his hotel room proved nearly fatal…for both of us. He graciously offered to share a nearly full bottle of Bushmills Black Bush Irish Whiskey. Never having had the pleasure, I was somewhat timid at first, but over a period of several hours I became more courageous. Our first several two-finger splashes soon became three, while the time interval between bent elbows became less and less. Questions and answers became more lengthy and convoluted, to the point where I promised I’d try to make us both sound brilliant, post-transcription. I also promised that if he were to expound on what his forthcoming book, Realtime Interrupt, was about, I wouldn’t print a word of it. More’s the pity. He spoke about a different approach to VR interfacing he had created for the book, that when presented to the Godfather of AI, Marvin Minsky, sent Minsky pacing back and forth across his living room, a fierce light in his eyes, then to stop and exclaim, “By God, Hogan, this just might work!” I wish I could share what Realtime Interrupt is about, but I’m sworn to silence. You’ll just have to read it to believe it. His most recent speaking engagement took place at the 1993 Annual Gathering of American Mensa in Orlando, Florida (July 1-4) where he chaired a writers’ workshop.

I wish to thank Jim once again for the time he spent (as well as for the Black Bush) and hope I’ve done a fair job of at least making him sound brilliant.

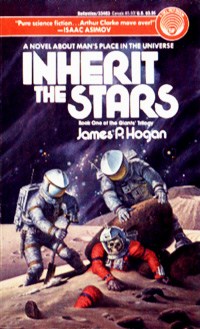

TANGENT: Inherit the Stars was published in 1977 and was your first book. How did you get in touch with Judy-Lynn del Rey, and what was she like as an editor?

HOGAN: I was living in England in the mid-seventies. First novels take a long time to write, and I’d been working on Inherit the Stars for some time. It’s like any other profession in that the first time you do it, you’re finding out how. But, at the time I was a sales executive in the computer industry in England, working for Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC), selling real-time systems to scientists, so my customers were physicists, chemists, astronomers, biologists, and so forth. I had a very basic interest in science to begin with. But my interest in writing science fiction began with the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. I didn’t understand the ending and I don’t think many people did. I enjoyed the movie tremendously. You know, when it was made in the late 60’s, the technical authenticity was tremendous. All the little details were great, and I was looking forward to it all being resolved in a nice, satisfying ending. But instead it degenerated into all this symbolism and mysticism which I didn’t understand. And so (smiling), being an argumentative white male I sort of bitched about all this. So the guys in the office, who had a living to make, got tired of me complaining about the movie and, I suspect, to shut me up said, “If you can do something better, then do it.” So I said I would, and then someone else said, “Yeah, but you’ll never get it published.” So I took the bet (we all bet money on it), went out and bought a typewriter, and began writing Inherit the Stars as a hobby in the evening.

HOGAN: I was living in England in the mid-seventies. First novels take a long time to write, and I’d been working on Inherit the Stars for some time. It’s like any other profession in that the first time you do it, you’re finding out how. But, at the time I was a sales executive in the computer industry in England, working for Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC), selling real-time systems to scientists, so my customers were physicists, chemists, astronomers, biologists, and so forth. I had a very basic interest in science to begin with. But my interest in writing science fiction began with the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. I didn’t understand the ending and I don’t think many people did. I enjoyed the movie tremendously. You know, when it was made in the late 60’s, the technical authenticity was tremendous. All the little details were great, and I was looking forward to it all being resolved in a nice, satisfying ending. But instead it degenerated into all this symbolism and mysticism which I didn’t understand. And so (smiling), being an argumentative white male I sort of bitched about all this. So the guys in the office, who had a living to make, got tired of me complaining about the movie and, I suspect, to shut me up said, “If you can do something better, then do it.” So I said I would, and then someone else said, “Yeah, but you’ll never get it published.” So I took the bet (we all bet money on it), went out and bought a typewriter, and began writing Inherit the Stars as a hobby in the evening.

When I finished the book I had absolutely no idea what to do with it, for while I’m a voracious reader, I wasn’t particularly into science fiction and so didn’t know the people, the editors, etc. Back in the 70’s DEC was sort of the renegade outfit compared to the more traditional companies like IBM or Honeywell. Where you could spot these IBM guys with their blue suits a mile away, or with their Honeywell manuals tucked under their arms, DEC people were very informal. People came in to work in Bermuda shorts, played guitar, worked until three in the morning. Somehow at that time DEC managed to combine the motivation and excitement of running your own business, which allowed the unfettered creative juices to flow. People could work with all the dedication of the entrepreneur, but with the protection of a big company. But anyway, DEC had a lot of talented people as well as its share of crazies, including the science fiction nut. So I asked around to find the science fiction expert at DEC and met this incredible guy named Ashley Grayson, who at that time was working in software support in the States. He went to conventions, knew editors and the whole SF scene. I called Ashley in the States. Eventually I flew to Cape Cod in 1976, met Ashley as a sales conference with manuscript in hand, flew back to England and forgot about it. And this is how green I was to science fiction: about six weeks later a letter turned up from a company I’d never heard of, called Ballantine Books, from a person I’d never heard of called Judy-Lynn del Rey. Ashley had lived up to his reputation, had gotten the book to Judy-Lynn, who read it and liked it and offered me a contract. And that’s the “How I Had It Tough in the Early Days” story.

TANGENT: What kind of editor was Judy-Lynn?

HOGAN: Superb. Tremendous. I think perhaps one of the most fortunate things to happen to me as a writer was having Judy-Lynn as an editor in the early years. She was very blunt, very forthright. Judy went straight for the chin and didn’t pull any punches, but that’s what the beginning writer needs. She was one hundred percent New Yorker. If you wanted a lot of ego stroking and false praise, Judy wasn’t the person. If you wanted to be taught how to write a book, to get a lot of silly, fuzzy illusions out of your head and see the business through reality, you couldn’t do better than Judy. She was terrific. She would tell you exactly the way it was.

I’ll give you an example. She liked Inherit the Stars. Her editorial letters were very perceptive. She had one of the most succinct and precise definitions of what constitutes a novel that I have ever heard. She said that a novel was a story. A lot of people don’t get that message; to them it’s a pulpit, an opportunity to design utopia, to tell people how things ought to be. No. It’s a story. A story about people. So, we’ve used three words already and how much garbage have we eliminated already? How many times have you heard somebody say, “I’ve got this great idea about a story,” and it’s the Earth collapsing under communism, or the Nazis this, or the environment that. Those are ideas. It is not a story. “A novel is a story about people we care about, who try to solve problems that matter.” That’s it. And when you think through each stage of that sentence it captures more of what a story is than anything else.

Now, some editors might pussyfoot, worry about stepping on your delicate ego, but not Judy-Lynn. She’d get on the phone and say, “We’ve got to talk,” and you’d hem and haw for a few minutes and then she’d come right out and say, “Hogan, if I was crazy about it I wouldn’t have called.” And that would stop me dead in my tracks.

TANGENT: Did she ask for many rewrites?

HOGAN: Well, as you’d expect, as time went on she’d hold your hand less and less because you could stand on your own better, but at first there were some changes in a book that needed to be made. I remember that her letters for the first book or two were superb examples of how to structure a novel.

TANGENT: Her changes were technical rather than ideological?

HOGAN: Yes. She wouldn’t argue with your opinion, she’d just tell you how to make a better novel out of your story. She wouldn’t argue with you about what you were saying unless, say, you went on and on for fifty pages and nobody cared what you were saying. Then she’d step in and say cut this or that, but never because she disagreed with you.

TANGENT: Who is your editor at Bantam?

HOGAN: Initially it was Lou Aronica, but he’s had some rapid promotions so now it’s Betsy Mitchell. I’m very happy with Betsy’s editorial skills. She’s very sharp. Maybe science fiction has found its new Judy-Lynn. Who knows?

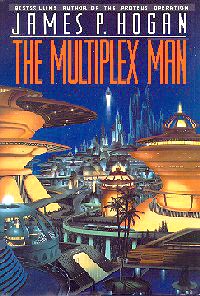

TANGENT: In your newest book, The Multiplex Man, your backdrop, the background through which the story weaves its way, seems to be a sounding board of sorts for your political and environmental views. Care to comment?

TANGENT: In your newest book, The Multiplex Man, your backdrop, the background through which the story weaves its way, seems to be a sounding board of sorts for your political and environmental views. Care to comment?

HOGAN: Yes, I expected that would upset a few reviewers. These questions are always difficult to answer, because if writing is anything it’s a process of never-ending personal development.

I’ve often been taken to task for things I’ve written, and when I say to someone that I didn’t write that and they say here it is in your book, I sometimes have to say that the person who wrote that doesn’t exist anymore. The person who wrote this book existed three years ago. And by the time the book hits print, it’s not that you’ve necessarily changed your opinions or anything, it’s just that it’s not the big bee in your bonnet it was at the time.

TANGENT: What are your politics now?

HOGAN: I’m a mix of both liberal and conservative. I’m certainly not an Anarchist and I’m not a Stateist, either. Anarchism probably kills more people than does totalitarianism. We need government. The government’s business is only taking care of things that can be achieved with laws backed by guns. So you need government to control criminals and deter aggressors; you need it to back up certain kinds of contracts—and very little else. But I’m open-minded. Some say we need government to build roads, etc. Maybe we do, I don’t know. I’ll listen to arguments, but I think my predisposition is to say, “Get them out of everything they don’t have to be in.” You don’t need laws backed by guns to educate children, or to take care of elderly people. I’ve seen socialism at work in Europe and I didn’t like it. I originally came to the States in the mid-70’s because the Callaghan government… Look, I thought the legacy of socialism in England had driven out all the bright people. It had destroyed initiative and originality. Mediocrity had triumphed.

I think I’m for the goals of the Democrats but the methods of the Republicans.

TANGENT: Well put.

HOGAN: The irony is that Lenin and his cohorts, if they were sincere at all (which is a separate debate)… I mean, who could be opposed to political justice, opportunity, an end to privilege? Nobody would dispute the goals of socialism. The irony is that if you look at 18th and 19th century German and French socialism, which was inspired by some of the most humane and well-meaning intellects, who could be opposed to giving everybody a chance at political equality? But just saying all the right words and declaring it to be true on an act of faith just doesn’t work. You judge something on the results it achieves, not the pious hopes it starts out with.

And with all of the Reagan/Bush years’ supposed faults, the S&L scandal and all the rest attributed to it by a very liberal media, I don’t think it was as bad as people are being told. These sorts of different philosophies tend to oscillate between upper and lower limits, and perhaps it’s too early to tell one way or another. Ten or twelve years really isn’t a very long time, actually.

TANGENT: What political itch were you trying to scratch with the politically correct Western world you used in The Multiplex Man?

HOGAN: Back in 1989 I was in what used to be Stalingrad, now Volgograd, when the Soviet Empire broke up, and the year or so before that I was at the European National SF Convention in Poland. And the interesting thing about talking to all these people who’d lived for generations under communism was their political astuteness. One of the great things about science fiction people is that they not only watch TV and read, they question. Unfortunately, you don’t see very much evidence of that in the population at large in America. The majority of people you meet see an official line on the TV that is so politically predictable. It seems to me that in America all your different media march to the same drummer.

But the Eastern Europeans and Russians have gotten used to ignoring the official line—they knew it was a lie. And it was this line of thought that led to this sort of inversion in The Multiplex Man, where it was the West that had become so totalitarian and the East that was more open. This wasn’t the thrust of the book, it was just a bit of backstage scenery that rather amused me.

The main line of thought that drove the whole book—going back to Judy-Lynn’s definition of a novel—was interesting characters sharing interesting situations. It is a man who finds himself in a very unusual situation. And what is the most bizarre situation you can find yourself in? Waking up one morning to find that you’re dead.

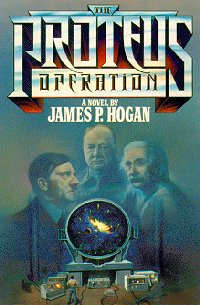

TANGENT: Do you like doing the research for your novels? I’m thinking of The Proteus Operation.

TANGENT: Do you like doing the research for your novels? I’m thinking of The Proteus Operation.

HOGAN: Yes, I do. However, that book was totally over-researched. I wrote the Prologue, then there was a year and a half before I wrote chapter one, and I probably only used about 5% of the research. Actually, I just got so involved reading about Fermi, Teller, Churchill—everybody who figured in the book. It was a wonderful year and a half studying up on World War II even though I used very little of the information I discovered.

TANGENT: You’re known as a hard-tech, mystery/puzzle kind of writer. Have you thought of writing anything out of this mold? Nano-technology seems all the rage now.

HOGAN: I just finished a story using nano-tech about two days ago. It’s going to appear in an anthology edited by Charles Sheffield, published by TOR Books. It seems Tom Doherty shares the delusion that science fiction writers know best how to solve the world’s problems. The theme, the thrust of this collection was going to be the world’s biggest problems and how to solve them.

TANGENT: What’s the title of this story?

HOGAN: Tentatively “Zap Thy Neighbor.”

TANGENT: What’s it about?

HOGAN: It’s about a newspaper reporter who gets drunk with a colleague of his, and they decide to write this gag piece and wire it into the newspaper, but they put the wrong destination code on it. It was supposed to end up in the editor’s pending stories file and instead it got sent to the immediate night priority file. By the time he gets to work the next morning of course the story is out and he’s upset everybody—the fundamentalists, the environmentalists, the abortionists, the gays, the anti-gays, the Nazis, the fascists, everybody. The title of the gag piece is “Assholes I Don’t Need in My Life.” But also going on is the fact that, through food additives, the society has pre-wired everyone’s brain with a particular neural code. If three people get your code and then transmit that code, you’re zapped. It’s a way to control society’s misfits, to make everyone more polite. If you get too far out of hand your private zap code gets published. You find everybody getting real polite real quick. Except that these two reporters get drunk and piss everybody off. I won’t tell you any more about it except to say that a lot of people die.

TANGENT: What novels are you working on now?

HOGAN: I’ve just finished a novel for Bantam called Realtime Interrupt. I’m just about to start a novel for Ballantine which is a sequel to Code of the Lifemaker.

HOGAN: I’ve just finished a novel for Bantam called Realtime Interrupt. I’m just about to start a novel for Ballantine which is a sequel to Code of the Lifemaker.

TANGENT: What does Realtime Interrupt deal with?

HOGAN: Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality. I’m not sure how much I can say without spoiling it so I’d better not say anything.

TANGENT: How did your recent article in the June Omni come about? The conservative, some might say anti-environmental viewpoints you expressed are sure to draw some criticism. Should we really not worry too much about the ozone layer?

HOGAN: If we want to eat healthy food, breathe clean air, and drink clean water, then hell, we’re all environmentalists. Nobody has a problem with that. But I’m skeptical about the official line on things like ozone and global warming.

TANGENT: Aren’t there just as many apolitical, scientific books to support the opposite view?

HOGAN: I don’t think they are apolitical. Everybody has an axe to grind. It’s a very complicated question to try to give a short answer to. I pretty much said what I believe in the Omni article.

TANGENT: So I take it you think the Rio environmental summit was a waste of time?

HOGAN: Oh, it was a complete circus. The U. S. could have done better. There were a lot of protocols in that agreement that haven’t been widely publicized, and my understanding is that the U. S. has surrendered its sovereignty in a number of key areas, to the point where the U. N. can now dictate environmental policy within the United States. You see, there’s a lot of people on the planet who think these problems are of a global nature, and I think that’s exactly what they’re supposed to think; therefore, the only way to solve them is with global authority. In other words, a world government. I think the underlying goal in a lot of these types of movements is to bring us closer to a world government, and I have a lot of reservations about that. Getting back to the question of the basic science that is being ignored, I must say that science is probably the only system of human belief in which it really matters whether what you believe is true or not. Science is a systematic process that enables us to decide reliably whether a particular belief is probably true or not. Most human belief systems, like religion, probably don’t care and it doesn’t really matter. Their concern is survival. They come from far more basic origins.

The primitive group that is squabbling and divided probably won’t survive. The group that believes in its one true God, or whatever, and rallies around it with fanatical conviction that they will win and go to heaven, they’ll survive. And that’s the purpose of religion; it’s a social group. It’s the essence of belonging to a group, with all of its ritual and custom. The important thing is to believe and to be seen to believe. What you believe isn’t really important. That’s why we can have a thousand different religions that are all equally viable. Whether they’re true or not really has nothing to do with it. They’re all survival strategies. And for most of human history this has been more important than knowing why the moons of Jupiter move the way they do.

TANGENT: Doesn’t this have a tendency to retard what we generally consider to be progress?

HOGAN: I’m a great believer in evolution.

The process of evolution is so universal and so powerful that it doesn’t only describe the emergence of biological species. The units that compete and are selected by the evolutionary process are really no longer individual units. These days it is modern social organizations that compete for survival: business corporations, religions, political parties, nations. And the same laws of survival apply. The same rules of competition and struggle will determine who will grow and profit, while others get eaten up or disappear. Actually, it can be argued that in the biological world parasitism is just as viable a way to survive as anything else. And we have social parasites as well; we have people who live who have no social use—they create nothing. Bureaucrats, governments, uh (smiling)– environmentalists?

Seriously, though, we have these grand stages of evolution; from the physical evolution of the Big Bang, to later chemical evolution as things cooled down and molecules got larger, to much later biological evolution as we know it, and now social evolution. It’s all part of one gigantic process where new laws come into being that are totally unpredictable from what came before.

Think about it; everything in nature has been an artifice in an attempt to stop evolution. Nature has been trying to stop evolution for fifteen billion years. When a species mutates to such a degree that it is no longer recognizable, it has become extinct. Every gene correction or mutation has been made to stabilize the species. They’re all an attempt to stop evolution. What I’m trying to say is that for fifteen billion years nothing has been able to stop evolution, and Greenpeace isn’t going to do it now.

TANGENT: Thank you very much for taking the time, Jim.

HOGAN: You’re more than welcome, Dave.

James P. Hogan interview copyright © 1993, 2010 by Dave Truesdale

All Rights Reserved.