“Recrossing The Styx” by Ian R. MacLeod

“Recrossing The Styx” by Ian R. MacLeod

“Advances in Modern Chemotherapy” by Michael Alexander

“Brothers of The River” by Rick Norwood

“The Revel“ by John Langan “The Tale of Nameless Chameleon” by Brenda Carre

“Mister Sweetpants and The Living Dead” by Albert E. Cowdrey

“Pining To Be Human” by Richard Bowes

“Epidapheles and The Inadequately Enraged Demon” by Ramsey Shehadeh

“The Lost Elephants of Kenyisha” by Ken Altabef

“Introduction to Joyous Cooking, 200th Anniversary Edition” by Heather Lindsley

“The Precedent” by Sean McMullen

Reviewed by KJ Hannah Greenberg

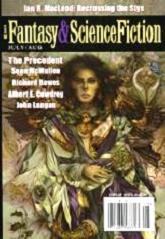

Fantasy and Science Fiction, consistently and predictably offers readers quality speculative fiction. This outlet’s authors reliably produce well articulated works on interesting topics, with the magazine’s July/August issue being no exception.

Per norm, the first short story in this issue, “Recrossing The Styx,” by Ian R. MacLeod, is stimulating. This bizarre tale finds a cruise ship’s tour guide escorting the undead and their very much living companions. Smitten by one of those companions, the man is forced to discern for himself the value of life and the value of life after life.

Although necrophilia, murder, and strange health care practices, such as companions having to constantly yield their organs and their bodily fluids to their dead compatriots, captivatingly fill the greater part of this text, this tale is really about intrapersonal values. Simply, MacLeod asks his readers to consider when ought individuals to aspire to positions of wealth and social status and under which conditions ought they to do so. The writer suggests that unchecked acquiescing to personal ambition is foolhardy and unendingly expensive. Whereas, for example, the main character does eventually acquire his lady love and she does eventually acquire eternal beauty and youth, the couple pays dearly for their purchases.

“Recrossing The Styx” is fresh, provocative and, at the same time, reflective. Today’s plastic surgeries and black markets for secondhand organs are but a few clicks away from the reality MacLeod portrays. What’s more, our times abound with persons willing to trade their identities and integrity for handfuls of sparkle. Fortunately, our times also flourish with thinkers like Macleod who can urge us away from cultural formaldehyde and from our tendency to celebrate moral necroses.

Despite the fact that certain of our authors can spring us from our most turbid thinking, Michael Alexander, as expressed in his novelette, “Advances in Modern Chemotherapy,” concurs with MacLeod that death might become exploitable. In Alexander’s grim story, a man, whose disease can only be responded to with palliative care, becomes aware of new supernatural abilities. It seems that persons hovering around life’s last stop can manifest extraordinary talents. What’s more, a cooperative of such souls has made it their business to identify similarly gifted individuals and to preserve their group’s knowledge.

The emphasis in this telling is not on the difficult ethical decisions that its players must make but on the wonder of the realms beyond, into which such persons seem to be able to spy. Although the topic of terminal illness is presented dourly, this story’s theme is hopeful; mankind might not be able to subjugate dreadful illness, but mankind can rise beyond the constraints of corporeal living.

Accordingly, I liked “Advances in Modern Chemotherapy.” Although I wish that the writer had focused more on the potential for human discovery and development of new agencies and less on the awfulness of incurable illness, I have a premonition that we’ll be seeing solid work from Alexander for a long time to come.

Like Alexander’s “Advances in Modern Chemotherapy,” the short story, “Brothers of The River,” by Rick Norwood, invites its audience to embrace far-fetched possibilities. Norwood gives over a tale of sibling rivalry that jumps beyond human skin and dwellings to mystical spaces where alternate perceptions must necessarily operate. One of the main characters is remarkable in his simultaneous generosity and zealousness. His equally magical, but more staid twin is at once also more tenacious. Each sibling, in his own way, aids the community into which they were born. Each sibling, in his own way, works to surpass his brother.

While it is entertaining to witness characters morph into nonhuman forms or to operate aided by nonhuman abilities, it is that much more satisfying to see their self-improvement. This tale, thus, is a telegraph from Norwood that life’s biggest challenges are not the externalized ones, but the ones located in our private spheres.

I experienced “Brothers of The River,” as a chewy bit flavored by exquisite settings and wondrous actions, and as an intellectually nutritious morsel able to posit our needs to conquer our inner worlds. Well written to a word, this story delivers an important message.

Even though the power of invention, of growing new ideas, is vital to story telling, creativity, the tweaking of old ideas, can be even more meritorious. In the novelette, “The Revel,“ by John Langan, readers are treated to a succulent playing around with point of view. This story of lycanthropic murder is told from the explicit perspective of an omnipotent narrator and from the implicit perspectives, correspondingly, of: a hero, a victim, a perpetrator, and a reader. Although this fiction’s creature of the moon remains vicious, furry and beastly, no matter the vantage point, the monsters in the other characters, as well as in the author and in the audience, also, satisfyingly, get exposed.

Readers are left to wonder whether champions of society are hideous in their obedience to customs, whether artists are repugnant in their uncensored acceptance of aberrations and whether unwitting brutes ought to be pitied rather than destroyed. Also, readers are left to think about whether or not our taste for speculative fiction, per se, fans the broadcasting of twisted thinking.

Any werewolf tale expressed via multiple angles is a gem of a read. We have too few tales like “The Revel” to shake up our assumptions.

Yet, this issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction yields readers another chance to explore our motives. In the short story “The Tale of Nameless Chameleon,” by Brenda Carre, a young girl bucks up against her society’s greatest leader in order to serve the greater good. The main character sacrifices her life as a flesh and blood human for the chance to champion the voiceless masses.

That the leader is a prince, that the main character’s position is that of an acolyte in a house of sages, some of whom are empowered with mystical talents, and that her mission is to literally transform her land’s ruler from a despot into a fierce, but needy, utensil, is almost irrelevant. The heroine represents not just the ability to triumph over personal adversity or the ability of society’s authentic watchdogs to protect the proletariat, but also the personal and collective price of keeping a culture honest.

Though it’s true I adore the descriptive language Carre employs to depict whore houses, study halls and the exactitudes of rulers’ clothing, what I admire most about this writing is the author’s prowess in palatably outlining a vital piece of sociology. I look forward to reading more of Carre’s speculative fiction as well as to reading her urban fantasies and women’s literature.

Another author whose texts I intend to seek out is Albert E. Cowdrey. His novelette, “Mister Sweetpants and The Living Dead,” is a highly entertaining narrative, which invokes a pompous author, the proprietor of a private security firm, a pretty wife, a zombie with a vendetta and other sumptuous characters. Throw in a charity event for bigwigs and a love affair between two lonely men and you’ve got a possible other dimension understood through the lens of burlesque.

In setting our expectations of how folk ought to live (or die, or stay dead) against our experiences of how folks actually live (or die, or stay dead), Cowdrey succeeds in serving a higher, altruistic vision by means of quick-witted, sexually suggestive prose. Further, thankfully, Cowdrey kills off “bad elements” of narrative in his plot and in his expression.

That is, since speculative fiction seems to spur many writers, their aunts, their bank managers and their neighbors to compete for superlatives among “high brow” rhetoric, it is toothsome to discover writing sufficiently advanced to making meaning via low humor. Readers yearning for fiction which entertains while insidiously poking at traditional cognitions will be happy to sample Cowdrey’s work.

In a related, but entirely different fashion, the novelette “Pining to Be Human,” by Richard Bowes trounces suppositions in favor of illuminating verities. Bowes’ main character, a probable victim of child abuse, who is urged to confront his demons and who is befriended by a therapist whom, herself suffers from the most toxic of human relationships, by tale’s end, can merely commit himself to a hospital where he is left drifting between “methadone and agony.” However, this main character does progress to literally behold the specters that have long made him their haunt.

“Pining to Be Human” is a coming of age story as well as a cautionary tale. On the one hand, this work traces the main character’s troubled development. On the other hand, this work shouts out the dangers of unmitigated sex and drugs. Throughout, this narrative waxes between cherishing the illusions concomitant to adolescence and urging readers to immediately take responsibility for their lives.

While the images in this story are spooky in their accurate reflection of too many people’s experiences, I found these representations concurrently poignant because of their power to display complex life passages. By bringing the darkness of teenage years to the fore, Bowes provides his readers a great advantage.

The next offering in this issue, the short story “Epidapheles and The Inadequately Enraged Demon,” by Ramsey Shehadeh is a very different sort of piece than is “Pining to be Human.” The latter is effective because of its gestalt. The former is effective because of its unsophisticated, differentiated components.

Shehadeh’s story is one of a cockled husband who hires a befuddled magic user to reclaim his wife. The woman, meanwhile, has taken up residence with a fierce demon whose displays of power, including pyrotechnics, are far less interesting than are the estranged gal’s coercions. She’s been working, for a long span, to manipulate the evil spirit away from fiendish tendencies.

That the mage’s familiar is an invisible chair, that his employer is missing a significant amount of hair and common sense, that the demon eventually, as an altruistic gesture, commits hari kari, are not, even in sum, as endearing as are the lines of dialogue between the misfits or as are the observations the characters make about the tortured souls populating the demon’s realm. Consider that the alienated wife attempts to surface the demon’s rage by sending him to converse with a civil servant or that the magic user’s attempts to disguise himself consist of a beard “made out of twine and goat hair and pasted to his real beard with epoxy.” The end result of such a mash of figures is a robust farce that sends up both the fantasy subgenre and the overly utilized figurative mode of “allegory.”

If more fantasy works mocked unlikely, extravagant, and improbable situations with proficiency and aplomb akin to Shehadeh’s, then speculative fiction would be lighter, more urbane, and altogether better. While we wait for that sea change, we can enjoy “Epidapheles and The Inadequately Enraged Demon.”

Alternatively, sometimes, we pursuers of fantasy and science fiction benefit from somber story telling. For instance, the novelette, “The Lost Elephants of Kenyisha,” by Ken Altabef, would be less striking if it was less meditative. A work that tasks itself with raising awareness about humanity’s indifference to killing off the planet can ill afford a flippant presentation.

In this tale of wild biology, a herd of phantom elephants troubles African communities that abide by poaching prohibitions and African communities that run rogue against those laws. As a result of the large ghosts’ rampages, hunting restrictions are lifted and additional pachyderms find themselves on the spirit side of the divide. Those dead elephants continue to act berserk until a British academic specializing in “psychical studies” and his African counterpart intervene. The scholars demonstrate that the departed elephants’ ire has been stirred because the mammoths are upset about their kind’s impending extinction. However, the elephants are made to understand that humanity will receive its comeuppance.

The havoc Altabef seems most interested in sending this shaman to repair, however, is not the mess made by the giant beasts, but the mess generated by mankind. The psychics are only able to disband the phantom herd after the ghoThis well executed story deserves a “thumbs up,” for its well-crafted writing. Rather than drone on in an essay marketed to kindred thinkers, Altabef astutely clothes his political agenda in fanciful fiction, thus making his ideas agreeable to a mindful audience.

As per satisfying audiences, it would be difficult to find readers who would not delight in the short story, “Introduction to Joyous Cooking, 200th Anniversary Edition,” by Heather Lindsley. This hoot of a brief fiction is a satirization of The Joy of Cooking. This story skewers the popularity of lab-regenerated plant and animal species as well as questions, aloud, the worthiness of faster food, i.e. of comestibles that are teleported directly into consumers’ digestive tracks and of balancing social differences. The narrator, for instance, claims that able hostesses ought to learn about “Gak-Glorian biochemical and psychosexual responses to various Earth foods [since such knowledge is] an obvious necessity for anyone planning an interspecies dinner party.”

By poking at the human folly indigenous to demographically tilted, but seemingly universally lauded, publications, “Introduction to Joyous Cooking, 200th Anniversary Edition,” succeeds in reminding readers that our priorities, even in nonfiction realms, might merit a bit of second guessing. In fact, this droll rejoinder allows that “cooking has never been without controversy, whether in matters of seasoning or the use of endangered ingredients.”

I love being lambasted about my species-specific prejudices while reading up on recipes for “[m]outh- and proboscis-watering dishes like Ca’ow, Sha’ep, and Ma’an” and while being made to appreciate that a post Armageddon Age will allow for “delicious slow roasts simply by leaving food outside.” I encourage folks to consume this tale and to seek out more of Lindsley’s provisions.

Whereas “Introduction to Joyous Cooking, 200th Anniversary Edition” is witty, Sean McMullen’s novelette “The Precedent,” is wise. In this dark tale of a resource-depleted Earth, a significant portion of the population is made to suffer ghastly deaths as punishment for their having left the ruling generation few natural reserves. The populous’ executions are appalling and the system of sentencing is unjust; any person who at all complied with his peers’ standards for consumerism is found guilty.

The main character, though, successfully appeals his death sentence on the basis of his previous attempts to vanguard ecological stewardship. His resulting punishment, ironically, is worse than death; the main character becomes iconicized as the measure to which others ought to have aspired. He is forced to live so that the plutocracy can justify a more pervasive genocide.

It’s interesting that McMullen employs horror to show the dreadfulness we might be inviting into our lives. It’s fascinating, as well, that like Altebef, McMullen espouses potential doom and gloom not through political forums, but through the pulpit of speculative fiction.

McMullen’s evocative tale is worth reading. Whereas I am still fumbling with a response to his implied accusation that we readers are incapable of making better choices than did his characters, I am grateful to this writer for raising such an uncomfortable subject.

In all, the July/August 2010 issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction is a fulfilling trip through horizons both near and impossible. I imagine that this publication will remain an exemplary venue for a long time to come. I look forward to reading more of its stories.