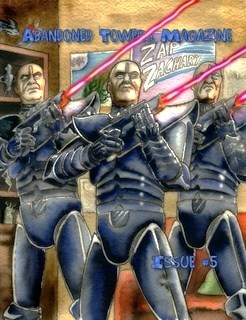

“Zap Zachary Returns” by Stoney M. Setzer

“Zap Zachary Returns” by Stoney M. Setzer

“Gold” by Arthur Mackeown“Ray Guns” by Doug Hilton

“Othan, Debtor” by Kurt Magnus

“The Horrors of War” by Chris Silva

“Mindforms” by Dal Jeanis

“Jeffery’s Story” by Guy Belleranti

“Final Score” by Bradley H. Sinor

“Riding to Hounds” by Thomas Canfield

“Copper-bottom’s Downfall” by Arthur Mackeown

“The Last True Gunslinger” by Y. B. Cats

“The Empty Chair” by Malcom Laughton

“ ‘ware the power” by Jack Mulcahy

“Call of the Northern Seas” by Normal A. Rubin

“Across the Plains” by Lou Antonelli

“Hobocop” by Kevin Bennett

“Odds Are” by Kevin Brown

“The Grave of Armond Balosteros” by E.W. Bonadio

“The Last Saguaro” by Doug Hilton

Reviewed by Maggie Jamison

Abandoned Towers #5 begins with a telling editorial in which editor Bill Weldon states: “Writing has no minimum standards save for the quirks of a few publishers.” Having read this issue from cover-to-cover, I am—unfortunately—forced to disagree. Or, at least, I am forced to believe that the editorial staff who oversaw this issue of Abandoned Towers should have adopted some minimum standards.

That’s not to say there aren’t some decent stories in this issue, but they are by far the minority.

The issue begins with the featured story “Zap Zachary Returns,” by Stoney M. Setzer, in which dried up actor Clint Adamson, once star of a hit sci-fi TV show, finds himself at the end of his career and the end of his rope. But all may not be as hopeless as it appears, when Clint is suddenly visited by some familiar faces.

This is not a great story: the characters are flat, the action is less than exciting, and the ending has a distinctive whiff of cheddar. It is, however, one of the better stories due mostly to its first half where the dialogue is well-written, and Clint is surprisingly sympathetic.

“Gold,” the first story in this issue by Arthur Mackeown, begins when long-time patron Will Saunders decides to travel on the recommendation of the local bookstore owner, Mr. Green. Spurred by an unrelenting sense of adventure, Will sets off with his new girlfriend to experience the locales that have captivated him in the books he reads. His experiences abroad have a profound effect on the doubting homebody, Mr. Green.

“Gold” is not a genre story, but it has a hint of that warm, fuzzy feeling anyone who has played and loved Myst might enjoy in its descriptions of Will’s travel journal, which Mr. Green receives. The setting feels cozy in the way it channels a Roald Dahl-era tone, but otherwise the story itself is a little bland.

“Ray Guns,” by Doug Hilton, follows Sam (MILBOT/III, S/N: 1), a highly developed android working as a spy for North Korea. After stealing bank information, Sam finds himself tangled in a web of intrigue as he tries to track down a man with blackmail ties the North Korean government wants to exploit. However, the man is more than just your average target, and Sam soon finds himself in over his head.

The beginning of this story, particularly the descriptions of Sam’s origins, was more enjoyable than its all-too-easy ending, in which all Sam needs to turn his deep-set loyalty programming is a patient lecture from the man who was just his target. Apparently androids are fairly impressionable.

Kurt Magnus’ story, “Othan, Debtor,” brings the fantasy genre into the story mix. Othan is a thief with a debt to repay to the mysterious Beetle Cult. When he’s called upon to fulfill that debt by killing a powerful prophet within the cult itself, Othan wonders if getting tangled up in cult politics is the healthiest option he has.

“Othan, Debtor” reads a little too much like badly-disguised gamer fiction, and has a distinctive mission-style/cut-scene feel to the narration. Given that as long as the copyrighted material is removed, Abandoned Towers is not against publishing game-based fiction, and may be exactly what this story is. That said, Othan isn’t a wholly unlikable character, and the plot has a clear beginning and end, which does put this one slightly above some of the other stories in this issue.

Chris Silva’s tale, “The Horrors of War,” recounts the fury of a raging battle, waged by the cubicle slaves of the corporate world. It’s a short tale, with little genre other than the imaginings of an epic battle, but it did make me smile after a long day of work.

“Mindforms” by Dal Jeanis, ventures out of the pulp science fiction arena and into the realm of decent world-building and decidedly non-human aliens in an underwater world. Thalen has come as a visitor to the world of the hive-mind slugs, the Zard, to learn what happened to his predecessor, Ruzeck. While searching for answers and collecting scent memories in his mind pods, Thalen befriends a one-sexed scout who desperately needs his help.

“Mindforms” is one of the better stories in this issue. Jeanis has created a bizarre, thoughtful world, unique alien life forms, and a compelling conflict. While there are points where the writing feels clunky, overall, it’s an enjoyable read.

“Jeffery’s Story,” by Guy Belleranti, is a murder mystery which comes in the form of the recorded statement of young Jeffery as he explains what happened when his father disappeared that day. This is a cute story, and though not revolutionary in its plot or characters, it is a decent, if predictable, read.

“Final Score,” by Bradley H. Sinor, can be summed up in a series of seemingly unrelated words: Lancelot, vampire, renaissance fair, serial killer, hard, and tough barmaid chick. Lancelot, now an immortal vampire, is hunting the killer of an ex-girlfriend at a modern-day renaissance fair to extract vigilante justice. In the process he meets Serina, a typically tough modern-fantasy girl who apparently exists in the story only to make feisty love to him at varying intervals, and to overcomplicate the plot with the addition of her thug ex-boyfriend.

To be honest, I didn’t initially finish reading “Final Score” because I was too distracted by Sinor’s repetitive use of the word “hard” to describe every action move:

“Serina slammed her knee hard into Michael’s crotch.”

“Serina punched him hard in the stomach.”

“Their lips met in a hard passionate kiss […]”

“[…] she murmured hard into his ear.”

“[…] the other man’s blade sliced hard toward Ashe.”

“He struck hard against Chalker […]”

I could go on, and on, and on. After I finally finished the story, I went back and counted: there are at least eleven uses of the word “hard” in this short story. Also, Lancelot has a magic leather jacket that he can apparently take off, and then have re-appear on him later, mid-battle, when he needs something to protect him from the cut of his enemy’s attacks. Style and logic are not strong suits in this story, and unfortunately, the story would be much better off if there were a snarky dark wizard mocking the cardboard characters the whole time.

Thomas Canfield’s story, “Riding to Hounds,” is a bizarre story bordering more on fantasy than science fiction, in which military helicopter pilot McIntyre finds himself thrown backward in time after a near-fatal crash. There, he becomes part of King Henry the Eighth’s court, whom he takes out on hunting expeditions for dinosaurs in the helicopter. This story might have worked for me if it were funnier, but as it is, it’s shallow and the action and characters aren’t developed enough to be engaging.

“Copper-bottom’s Downfall,” the second story in this issue by Arthur Mackeown, is a non-genre, slice-of-life (sort of) story about a boy named Arthur and his run-in with the school bully, Nicholas. It’s a painfully flat story, with no development, a conflict resolves itself with no effort on the part of the main character, and without any new take on the bully-versus-protagonist storyline.

“The Last True Gunslinger,” by Y.B. Cats, is an out-and-out Wild West story about a gunslinger named “Red Bandana” for the red bandana he always wears to hide his face. Though plagued by a dimwit brother, and a nefarious priest, Red Bandana is more than he appears, and Susanna the saloon girl is tired of keeping his secret for him. When Black Bart comes to town looking for a fight, Susanna gets an idea that will help all of them out of the mess Red’s unwittingly created.

“The Last True Gunslinger” isn’t the greatest story, but Susanna is likable despite the generic plot devices, and the conflict is interesting enough to move the story forward at a decent pace.

Malcolm Laughton’s tale, “The Empty Chair,” is a semi-surrealistic tale following an unnamed main character on a dream-like expedition through a photograph into a past version of Glasgow. Here, he meets two men he’s known before in other photograph worlds. One is tolerable company; the other, a danger to the protagonist’s life.

This story reads more like a transcribed dream than a story, complete with inexplicable occurrences that seem to play no part in the conflict (if there is one), mysteriously undeveloped characters that appear and disappear without clear reason, and an aimless plot, all wound up into what feels like the result of a photo-inspired writing prompt.

“‘ware the power,” by Jack Mulcahy, is a high fantasy story involving “Magic” and the merciless battles between the Raheshis and the Aurigans. Sergeant Kyntha and Lieutenant Mikhaila (dubbed “the Pet” for her status as aide to the General) are the last free members of their troop after a thwarted ambush on a Raheshi slave caravan. Together, they must overcome their personal differences to rescue their comrades from the caravan slavers.

“‘ware the power” is a classical sword and sorcery story, complete with daggers, crossbows, flaming blue torrents of “Magic,” witches, and wholly evil villains. It’s one of the better plotted stories in this issue, and the character development is a notch above the others, making it—overall—a satisfying read, if not particularly original. Unfortunately, it appears that the editorial team cut off the last paragraph prematurely.

“Call of the Northern Seas,” by Norman A. Rubin, is a retelling of the Legend of Sedna, the Inuit goddess of marine animals, according to the preface. In this telling, Sedna marries a bird-spirit by accident, having fallen for his human-form, and due to her misery must be rescued by her father. In the process, however, her father angers the god and must make the ultimate sacrifice to escape. The story itself is told in a legend format, which leaves the reader somewhat distant and uninvolved. Having read some of the other versions of this story, it doesn’t appear that Rubin added much, though the little poetic cut-away passages are pleasant.

In Lou Antonelli’s story, “Across the Plains,” Bobby and Sean get a glimpse into a world unknown to them when they sample some dried mushroom bits they find in an old Indian medicine bag. When the visions stop for Sean, however, something dark seems to have remained inside Bobby. For me, this tale didn’t hold much interest. The conflict occurs only because the characters aren’t very bright, and the outcome is predictable.

“Hobocop,” by Kevin Bennett, follows paranoid drunkard Duncan Hainstock after a night of heavy drinking which finds him inside the belly of a street-patrolling, hobo-snatching government-owned robot. For me, this story fell short. The attempts at humor just didn’t work, the writing was clunky, and the vast swatches of dialogue in which characters explain everything failed to hold my interest.

“Odds Are,” by Kevin Brown, is a modern-day horror story that explores what fear alone can do to a man and his family, and what escape for one can mean for another. After receiving a call late at night two weeks past, threatening a gruesome murder to whatever family lives at his street address, the unnamed protagonist is overwhelmed by dread of this event. Despite others teasing him for overreacting to a prank call, that the odds of something like that happening are slim, the main character decides to pack up his family and move. He’s had slim-chance encounters before, and he’s not going to take the risk.

“Odds Are” may not be genre enough for some readers, but it is far and away the best story here. Brown weaves a careful, social web that builds a refreshing amount of dread around what could be a totally harmless situation. Brown’s characters are well-rounded, believable, and sympathetic. The atmosphere of the story is deliciously eerie.

E. W. Bonadio’s tale, “The Grave of Armond Balosteros,” takes place in an old graveyard in Spain, where a young soldier encounters the storytelling spirit of a man wrongly executed during the Napoleonic wars. The ghost relates his tale of woe while the soldier listens, gradually revealing how a local hero from those times may not be as great as his tombstone might suggest. In my opinion, this story would have been more engaging if it had been told in-action, rather than recounted long after the events described have taken place. As it is, the story feels distant and the ending is expected.

“The Last Saguaro,” the second story by Doug Hilton, occurs in a near-future Arizona, and follows Sah-wah-roh Joe on his night watch over the U.N.-sanctioned Sonoran Desert World Wildlife Preserve. His job is to protect the last remaining Saguaro cactus from cactus poachers, using UAVs and high-tech binoculars. The story isn’t particularly thrilling, perhaps as a result of the author not taking quite enough time to make the reader care about the cactus’ survival, but the world-building Hilton invests some time in is detailed and interesting.

Overall, this issue of Abandoned Towers is a mixed bag, heavily weighted toward the poorly written and poorly edited. There are a handful of decent stories, however. I would recommend “Mindforms” and “Odds Are” for those readers with a taste for solid world-building, well-developed characters, and grammatically-aware writing. Out of the nineteen stories, I found those two to be the most entertaining. The magazine as a whole could use a good proofreading team.