“The Night Clerk” by Ray Garton

“The Night Clerk” by Ray Garton

“Stretcher of Faces” by Fred Venturini

“Fallout” by Jesse Click

“Poetic Justice” by Brian Kutco

“The Book Says” by Michelle Howarth

“Aftertaste” by A. David Zapata

“The Hedgehog Prince” by Rhian Waller

“Lucky Number” by J. David Fry

“A Stone’s Throw” by K.J. Hannah Greenberg

“From Behind the Tablecloth” by Nathan Wellman

“Nemo And Kafka In Limbo” by Gary Inbinder

“Bender” by Michael Laquerre

“That Which Rises” by Chris Ewing

“Moving Parts” by Louise Morgan

Reviewed by Maggie Jamison

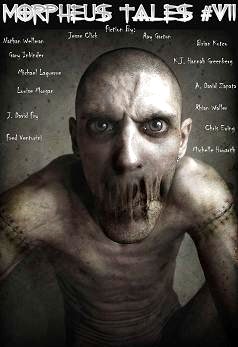

Behind the intimidating cover, Issue #7 of Morpheus Tales presents a gathering of thirteen (perfect number!) stories with subjects ranging from cults, to the apocalypse, to disturbing talents, and even a regular trip to a convenience store. But one thing all of these stories have in common is a dark thread, sometimes overt, sometimes subtle. This particular issue is a bit of a mixed bag: while most of these stories are solid in their storytelling, there are some that falter with clichéd plots, while others transcend the standard, weaving tales that will grip the reader like the burrowing eyes of the magazine cover.

The issue begins with Ray Garton’s “The Night Clerk,” in which Marcus Miller—an average Joe with his share of bad habits—goes to pick up some beer and some smokes from his local convenience store where he encounters an overly honest clerk. But telling the whole truth to someone who doesn’t want to hear it often leads to trouble.

“The Night Clerk” is a good opening story. It’s got a quick pace, tight writing, and Marcus is a sympathetic character with whom it’s easy to relate. The only issue that some readers may have with this story is that it’s almost not a horror story. It’s got a shot of violence in it, but other than that, it’s a relatively mild tale with little speculative element.

“Stretcher of Faces” by Fred Venturini is a dark, surrealistic tale that follows Jacob through dark woods, memories, dreams, and future events as he flees a human-like creature that revels in the nasty art of stretching skin.

There are a lot of things that should highly recommend “Stretcher of Faces” to fans of surrealistic dark fiction. Particularly, the imagery of those whose faces have been torn-off or stretched by the thing referred to as “the dweller” are visceral and memorable. However, the plotting of the story comes off somewhat confused as the narrative jumps from scene to scene in rapid succession leading to the end, and at times, those abrupt transitions had difficulty maintaining a suspension of disbelief for this reader.

“Fallout” by Jesse Click is the quintessential apocalypse story: Ethan has lived through the end of the world, which came in the form of a multitude of volcanic eruptions clogging the air with killing, smothering ash, resulting in a destroyed and broken world on the brink of starvation. The last of his surviving family, many of whom—once dead—Ethan had to eat for nourishment, Ethan meets a helpful stranger on the road to nowhere who may not be as altruistic as he first seems.

“Fallout” was one of the weaker stories in this issue. The ending is predictable from the first mention of cannibalism, which results in a plot that cannot build any sense of dread as Ethan walks with unwavering and unexplained trust to the expected conclusion.

In “Poetic Justice” by Brian Kutco, young Spike must earn his adulthood by taking the life of the animal his family has kept to slaughter. With his father egging him on, and his mother waiting in the kitchen, Spike must decide if he will kill the thing, no matter how innocent and afraid the animal looks at the sight of his knife.

On the heels of the last story, “Poetic Justice” also falls into the trap of being just a little too predictable in its outcome. The complete lack of description of the animal is a tip-off from the start, and the twist at the end is all to familiar to those who have ever watched the New Year’s Marathon of The Twilight Zone.

“The Book Says” by Michelle Howarth is a dark tale of superstitions, cults, pursuit of perfection, and skin. Lucy is certain that the day will be far from typical: her underwear tells her so with snapping clasps, sudden holes, and pinging straps. First a lover’s thoughts, then bad luck, then a gift: what could all these signs have in common?

“The Book Says” is a delightfully wicked story, with a pinch of dark humor and an eerie underlying tone. The language of the story is well executed, and the ideas are fresh. The sense of dread that permeates the story, while subtle in some places and not subtle at all in others, will keep readers turning the few pages of this brief, but satisfying story.

A. David Zapata’s story, “Aftertaste,” begins by introducing Todd Dimwalt as he holds an armful of his own intestines, contemplating his approaching demise. After a night out drinking with his best pal, he hadn’t expected to have a run-in with a monster in a basement. Or is it a monster at all?

“Aftertaste” is not a predictable story, but it’s also not particularly believable either. It runs into the all-too-common problem of having a character who makes inexplicably stupid decisions and pays the ultimate price because of them. While Todd Dimwalt never quite says “Let’s split up,” the fact that he’s named Dimwalt says a lot. There’s a hint of dark humor underlining this story, however, and other readers may enjoy it more for that and not mind the lack of plausibility.

“The Hedgehog Prince,” by Rhian Waller, is a dark fairytale about the princeling of a shapeshifter and his struggle to find the woman of his dreams. His father, Hans-the-King, knows the pain of being a strange creature amidst the realms of humans, and his greatest fear is that his son will die of loneliness. Putting together a classic ball full of beautiful women, he hopes to find his son just the right girl, but when Prince-Hog finds his true love, things are not well in the kingdom.

“The Hedgehog Prince” is the lightest story in this particular issue, with only a hint of tragic darkness rather than the gritty shadows of the other tales. While the idea was an interesting one, the style—and perhaps the length restrictions—made it difficult to personally engage with the characters and their struggles, and in the end, left this reader feeling unsatisfied.

In “Lucky Number,” by J. David Fry, the unnamed main character finds himself caught between a beautiful stranger and a Keno bet. While Julia seems like a fun time, and seems like she might just be willing to let the main character have a fun time too, there are some people who just take Keno too seriously.

“Lucky Number” is a tidy short story. It creates a good sense of place, has some skin-crawling developments, and the main character is an understandable guy. It’s a whirlwind because it’s short, but it doesn’t feel unfinished by the end. It’s a quick and dirty little tale that delivers good entertainment.

“A Stone’s Throw” by K.J. Hannah Greenberg is a dark tale of love long past, and opens with the sudden and unexpected death of Marsha’s husband by a rock caught in the lawnmower. But instead of being shocked, or frightened, or even slightly sad, Marsha quietly accepts and relishes the outcome.

This story is brief, not even a full page long, but in its compactness there’s still a sense of witnessing something awful in inaction. The ending was a bit abrupt, and while there appears to be a slight attempt at dark humor, it feels as though there could have been more story to this very short tale of marital liberation.

Nathan Wellman’s story, “From Behind the Tablecloth,” begins with a scent of perfume and the sudden return of Dan’s wife. But their estrangement is one caused by sudden death, insanity, and violence, and her reappearance in his life after her escape from the mental institution he’d had her put in is not something he’s going to enjoy.

“From Behind the Tablecloth” is a solid, if brief, horror tale, and it brings some nice suspense-building to the table. The ending is a bit too tidy, however, and some may feel too convenient in that sum-it-all-up kind of way, though it is fitting with the character.

“Nemo and Kafka in Limbo” by Gary Inbinder begins on the barren shores of the River Styx, and follows Nemo and Kafka the Cat in their process of determining which step comes next. Either they cross the river via the boat run by Charon, though not having any Greek oboloi will mean paying the debt in a thousand years of additional torment, or continue wandering in the barren Limbo in the hope of finding something better.

Unfortunately, “Nemo and Kafka in Limbo” is a difficult story in which to engage. The style and Nemo’s manner of referring to himself in the third person tends to break the flow of the story. On top of this, the plot is exactly the same as the dog and heaven episode of The Twilight Zone, and will be instantly recognizable to anyone familiar with that storyline. While the ending was not predictable, it was disappointing in its familiarity.

“Bender,” by Michael Laquerre, takes place at a dinner party during which the host and hostess present their talented daughter, Lucy, to perform a trick she can do with a spoon. The little girl can close her eyes and a moment later, the spoon twists out of shape. While the guests are impressed, Lucy’s mother is clearly afraid of the child who can wield not only such power over spoons, but over humans as well, and Lucy is tired of being told what to do.

“Bender” is a fun take on the old telekinesis trope of gifted children bending spoons with their minds. It’s dark, it’s well-crafted, and it’s very enjoyable. The accompanying illustrations also add an edge of eeriness, though the story does an expert job of channeling its own dread.

In “That Which Rises,” by Chris Ewing, Andrew meets up with his brother Joseph to help him rob a grave in a small New England town. But when he sees the strange runes on the tall pillars surrounding the grave Joseph has selected, Andrew isn’t so sure this is going to be a great plan. Particularly when things start getting weird.

“That Which Rises” could have been a good story, however there were so many typos and the style so strained that it was difficult to focus on the tale itself. While the grammar may not have been the author’s fault, and may just emphasize the need for this magazine to get a second proofreader (badly), the story itself just doesn’t flow.

The final story, “Moving Parts,” by Louise Morgan, is about a strange house and its equally strange new owner. But while the narrator has found the disappearing and re-arranging rooms to be nothing more than a slight nuisance—and at times, even helpful!—the narrator has her own reasons for appreciating things that disappear, particularly if its her past.

“Moving Parts” is far and away one of the strongest stories in this issue. Tucked away at the end, it’s a force of elegant language, bizarre symbolism, unique concept, and eerie mood. The narrator herself is questionable in her reliability as the story’s only perspective, but it’s a wonderful counterbalance to the house itself, which is also sinister and unreliable. For those who like fast-paced stories, this tale may be too slow, but for those who appreciate careful and subtle storytelling, this story will not fail to please.

Morpheus Tales‘ website can be found here.