“The Voyages of Sinbad” aired on June 7, 1953 and was episode #199 from one of radio’s most dramatic, popular, and long-running shows, Escape (1947-1954). The stories of Sinbad the Sailor are taken from Sheherazade’s One Thousand and One Nights (aka in various English versions as The Arabian Nights, from its first rendering in 1706), and come to us in the West primarily through Sir Richard Burton’s now accepted 1885 translation.

“The Voyages of Sinbad” aired on June 7, 1953 and was episode #199 from one of radio’s most dramatic, popular, and long-running shows, Escape (1947-1954). The stories of Sinbad the Sailor are taken from Sheherazade’s One Thousand and One Nights (aka in various English versions as The Arabian Nights, from its first rendering in 1706), and come to us in the West primarily through Sir Richard Burton’s now accepted 1885 translation.

From the original literature, Sinbad’s seven voyages begin, and each are framed, by the opening story “Sinbad the Porter and Sinbad the Sailor,” wherein the now wealthy Sinbad the Sailor plucks from the street and invites the lowly, hard-laboring Sinbad the Porter into his plushly appointed home and relates each of his adventures, hoping, thereby, to inspire his namesake Porter to advance his position in life through lessons learned through his travels. Allah be praised.

Sinbad’s home is timeless Baghdad, Iraq, pseudonymous with Mesopotamia, historically regarded as the cradle of civilization. This rich, ancient civilization’s eastern border shoulders against what once was known as ancient Persia (now Iran–and indeed, Iraq was under Persian control until the 7th century A.D.), their ancient cultures and histories for thousands of years being inextricably intertwined in the areas of war, religion, myth, and numerous cultural and scientific achievements. Sheherazade’s 1,001 tales (woven from many collected ethnic folktales and myths from across the Middle East and its environs, including Egypt and India) can be traced back to the 9th century, the initial framing tale being ascribed to Persian origin. Capsule history lesson concluded, Sinbad’s point of departure for his voyages is the Iraqi southern port city of Basra. It seems as if Sinbad is forever getting shipwrecked during his exotic travels, and in this radio play we find him shipwrecked once again, to be rescued in yet another strange land.

“The Voyages of Sinbad” is adapted from the fourth of Sinbad’s original seven tales, and while reasonably accurate, there is one instance where the writer, Antony Ellis, took a bit of artistic license and switched Sinbad’s fellow captive and doomed companion (as you will soon hear) from a woman to a man. We leave it to the listener to arrive at his own surmise as to why the gender switch was made, but note that this was written in the 1950s, when contemporary American sensibilities toward women (for wont of another euphemistic turn of phrase) were different than today’s.*

*[Indeed, while there is certainly no direct evidence of this from any source, it is interesting to note that Tom Godwin’s classic SF story “The Cold Equations” from the August 1954 Astounding Science Fiction (published just a scant year after “The Voyages of Sinbad” hit the airwaves) — where a female is sacrificed for the greater good — and at the direct suggestion of editor John W. Campbell, Jr. for reasons directly related to his intuitive reaction of his readership as he perceived it in the 1950s, that both Antony Ellis and John W. Campbell were a product of their time. Yet, while both operated within the same time frame and contemporary societal expectations involving women (and men) in certain situations, one chose to alter a timeless story to cushion period views toward the death of a woman, while the other (Campbell) chose to confront those very same views and expectations in a stark and brutal manner, perceiving correctly the dramatic impact–story-wise–it would have on his readership. We can’t help but wonder if John Campbell was a radio listener in the early 1950s (as many still were, television being still in its infancy), heard this broadcast, and knowing his contrary, ever-questioning intellect, asked for this crucial change in Godwin’s now classic story. Whether Campbell listened to this episode of Escape or not is irrelevant, a mere bit of speculative mind play. But the diametrically opposed views of how audiences might view the death of a woman in either situation, given the 1950s mindset, is certainly telling, as writer Ellis and editor Campbell chose different paths from the identical set of cultural expectations, given their venues–one radio, the other an SF magazine. One the safe and tame, the other the challenging, emotionally sympathy-evoking charged, and (now) controversial. Though “The Voyages of Sinbad” and “The Cold Equations” were aired or printed within a year of each other, which of the two is still talked about and debated endlessly after almost 57 years (at least in SF circles)? Sheherazade’s 1,001 tales will surely remain as timeless and unchanged in our collective memories as ever, and Ellis’ slight revision will, for the most part, go unnoticed and forgotten. But it is “The Cold Equations” that still, and in times to come, will spark the never-ending debate John Campbell kindled into flame with his suggestion to make Godwin’s sacrificial lamb a woman.]

Though Sinbad was an adventurer, and as portrayed in the movies a lovable rogue, he was first and foremost a thief and general all-around rapscallion, and while some of the numerous movies made from his thrilling adventures portray him with a thieves’ sense of honor—and even a bit of nobility—he wasn’t above begging for his own life if the situation required he do so, and killing (even women) was certainly an option. The movies, for the most part, neglect this downside to his personality. Not that I’m complaining; it makes for terrific, romanticized entertainment, of which I am a staunch adherent. We (rightly or wrongly) feel akin to the likable anti-hero.

Numerous movies around the world and in many languages have been made of Sinbad the Sailor’s exploits over the years. Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. (1883-1939–photo at left) starred in one of–if not the–first of such pictures, with his swashbuckling, acrobatic, devil-may-care performance in the silent film classic Thief of Bagdad (1924). The story (conception) was from Fairbanks (as by Elton Thomas), was written by Lotta Woods, was then adapted by James T. O’Donohoe, and the final screenplay was written by Achmed Abdullah. The movie photo at bottom shows Fairbanks and love interest Julanne Johnston as they sail over Baghdad on their magic flying carpet in one of the films iconic scenes. (The background sets of Baghdad are fake, of course, but Fairbanks and Johnston are true images.)

Numerous movies around the world and in many languages have been made of Sinbad the Sailor’s exploits over the years. Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. (1883-1939–photo at left) starred in one of–if not the–first of such pictures, with his swashbuckling, acrobatic, devil-may-care performance in the silent film classic Thief of Bagdad (1924). The story (conception) was from Fairbanks (as by Elton Thomas), was written by Lotta Woods, was then adapted by James T. O’Donohoe, and the final screenplay was written by Achmed Abdullah. The movie photo at bottom shows Fairbanks and love interest Julanne Johnston as they sail over Baghdad on their magic flying carpet in one of the films iconic scenes. (The background sets of Baghdad are fake, of course, but Fairbanks and Johnston are true images.)

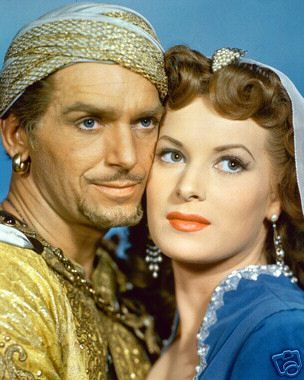

In 1947 Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (1909-2000) reprised his father’s role as Sinbad in the technicolor adventure Sinbad the Sailor, where we are given an “eighth” voyage of Sinbad. In this lavish costumer (short on plot, but a visual treat), Sinbad discovers the treasure of none other than Alexander the Great. Along with Fairbanks, Jr. it starred the stunningly gorgeous Maureen O’Hara (1920- ) and Anthony Quinn (1915-2001).

In 1947 Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (1909-2000) reprised his father’s role as Sinbad in the technicolor adventure Sinbad the Sailor, where we are given an “eighth” voyage of Sinbad. In this lavish costumer (short on plot, but a visual treat), Sinbad discovers the treasure of none other than Alexander the Great. Along with Fairbanks, Jr. it starred the stunningly gorgeous Maureen O’Hara (1920- ) and Anthony Quinn (1915-2001).

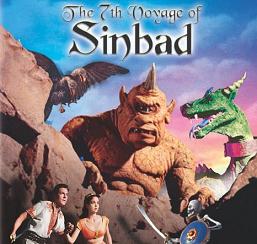

The late Kerwin Matthews (1926-2007, photo at right, confronting Sokurah the Magician as played by Torin Thatcher) starred in 1958’s Ray Harryhausen special-effects extravaganza The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, another classic inspiring a new generation of Sinbad fans. The second (color) photo at bottom shows Matthews dueling with one of Sokurah’s sorcerously animated skeletons deep in his mountain lair. It was this movie that introduced me to the colorful, picaresque, derring-do world of adventure, fantasy, and life-like monsters such as the magically transformed serpent woman, the Roc, the horned Dragon, and the giant, treasure-hoarding, flesh-eating, one-eyed Cyclops, when I was but a lad of eight—the year the movie was released. (Our cub scout troop leader had somehow miraculously obtained a copy of the film, and our entire troop–with parents–viewed the movie in the grade school auditorium, displayed in (almost) its full theater size from the combined auditorium/gym’s stage.) Kerwin Matthews played a spectacular, I-wanna-be-like-him, Sinbad, handsome and heroic–who would brave seemingly insurmountable dangers to recover his beloved miniaturized princess from the evil Sokurah. I was saddened to hear of his death in 2007, when he passed away in his sleep at age 81. Matthews retired from his film career in 1978. Somewhen about that time he moved to San Francisco and opened a clothing and antique shop. He was survived by his partner of forty-six years, Tom Nicoll. I’ll never forget Kerwin Matthews impact on me in his role as Sinbad in this film.

The late Kerwin Matthews (1926-2007, photo at right, confronting Sokurah the Magician as played by Torin Thatcher) starred in 1958’s Ray Harryhausen special-effects extravaganza The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, another classic inspiring a new generation of Sinbad fans. The second (color) photo at bottom shows Matthews dueling with one of Sokurah’s sorcerously animated skeletons deep in his mountain lair. It was this movie that introduced me to the colorful, picaresque, derring-do world of adventure, fantasy, and life-like monsters such as the magically transformed serpent woman, the Roc, the horned Dragon, and the giant, treasure-hoarding, flesh-eating, one-eyed Cyclops, when I was but a lad of eight—the year the movie was released. (Our cub scout troop leader had somehow miraculously obtained a copy of the film, and our entire troop–with parents–viewed the movie in the grade school auditorium, displayed in (almost) its full theater size from the combined auditorium/gym’s stage.) Kerwin Matthews played a spectacular, I-wanna-be-like-him, Sinbad, handsome and heroic–who would brave seemingly insurmountable dangers to recover his beloved miniaturized princess from the evil Sokurah. I was saddened to hear of his death in 2007, when he passed away in his sleep at age 81. Matthews retired from his film career in 1978. Somewhen about that time he moved to San Francisco and opened a clothing and antique shop. He was survived by his partner of forty-six years, Tom Nicoll. I’ll never forget Kerwin Matthews impact on me in his role as Sinbad in this film.

Needless to say, when I came across “The Voyages of Sinbad” on one of my Escape CDs I could only hope the story was worthy, and that the reproduction quality was good. I was rewarded on both counts. I won’t say much about the following dramatization, except to say that it opens in Baghdad, and in the tale as related from Sinbad the Sailor to Sinbad the Porter, you’ll find adventure in a strange land (with even stranger customs), love, treachery, violent death, and a close scrape with the mythical and deadly Old Man of the Sea—from whom no man has escaped—except Sinbad the Sailor!

The erudite classic music lovers among you will appreciate the apropos background music as that of composer Rimsky-Korsakov, from his Symphonic Suite (Op. 35) Sheherazade (1888).

Play Time: 29:31