“The Black Museum. A Repository of Death. Here in the grim stone structure on the Thames which houses Scotland Yard is a warehouse of homicide, where everyday objects . . . all are touched by murder.”

“The Black Museum. A Repository of Death. Here in the grim stone structure on the Thames which houses Scotland Yard is a warehouse of homicide, where everyday objects . . . all are touched by murder.”

The Black Museum (1952) aired “The Raincoat” (in the United States and as near as historians can reasonably ascertain) on January 22, 1952. This is only the 8th episode we’ve run of this show (the last being in August of 2020), so a bit of background is in order for newcomers to this sometimes grisly program. First of all, the name the Black Museum was coined in 1877 by a reporter for London’s The Observer newspaper, though the museum had opened in 1875 with the official name of simply the Crime Museum. It is the oldest museum in the world to display only artifacts of crime and is still known today by its official name of the Crime Museum despite the more colorful name given it by The Observer. The museum is not open to the public and is used primarily for instructional purposes for police training, but has had special visitors the likes of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

The Black Museum was one of four similar shows produced by Harry Alan Towers (1920-2009) under his Towers of London label in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Towers, a native born Britisher, would also produce popular radio fare like Secrets of Scotland Yard, Fabian of the Yard, and WHItehall 1212. All four shows centered around stories from the files of Scotland Yard, and New Scotland Yard’s famous Crime Museum, which was popularized in crime novels as the Black Museum. While all but Fabian of the Yard are verified as being produced and syndicated in Britain for future syndication, it is interesting to note that, according to the Digital Deli Too website entry, “WHItehall 1212 was a National Broadcasting Corporation production written by Lights Out’s famous scriptwriter Wyllis Cooper….” Three of the four shows, The Black Museum among them, would wrap their stories around an artifact from the museum, recounting in dramatic form the infamous crime associated with said artifact. Secrets of Scotland Yard kept to historical facts quite closely, and while a fascinating listen and quite popular, didn’t have the flair or melodramatic effect the likes of Orson Welles (1915-1985) would bring to The Black Museum as the host and narrator of each of its 52 episodes. And while The Black Museum also kept to the historical record surrounding each case, it would play a little fast and loose with them (or perhaps embellish them is the proper word) for dramatic effect, and it didn’t hurt that the show–unlike the others–drew its material solely from murders, thus guaranteeing the audience a chilling half hour. Overlay the grim stories with the somber, virtually hypnotic tones of Orson Welles and you’ve got a winner.

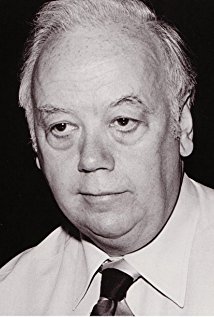

Speaking of Orson Welles, one might be given to wonder how he came to write some of, and host and narrate all of the episodes of The Black Museum, which were produced in the UK. It seems that Welles decided to take an extended “vacation” in England due to several professional and personal problems, including some “requests” from the Internal Revenue Service. So the American loss turned into Harry Alan Towers’s gain (Towers’s photo at left 1948, at right circa 1984), and he set Welles to work, a profitable solution for both parties. Welles would also work on two other Towers productions, perhaps the most well known to the American radio audience being The Lives of Harry Lime (or The Third Man.) The Third Man was a 1949 film noir British production set in post-World War II Vienna, with Welles playing the Lime character. Written by Graham Greene, it has attained classic status for its stylish portrayal of a decaying and corrupt Vienna, so Towers was striking while the iron was hot and rode the coattails of the film with Welles starring in the radio adaptation.

Speaking of Orson Welles, one might be given to wonder how he came to write some of, and host and narrate all of the episodes of The Black Museum, which were produced in the UK. It seems that Welles decided to take an extended “vacation” in England due to several professional and personal problems, including some “requests” from the Internal Revenue Service. So the American loss turned into Harry Alan Towers’s gain (Towers’s photo at left 1948, at right circa 1984), and he set Welles to work, a profitable solution for both parties. Welles would also work on two other Towers productions, perhaps the most well known to the American radio audience being The Lives of Harry Lime (or The Third Man.) The Third Man was a 1949 film noir British production set in post-World War II Vienna, with Welles playing the Lime character. Written by Graham Greene, it has attained classic status for its stylish portrayal of a decaying and corrupt Vienna, so Towers was striking while the iron was hot and rode the coattails of the film with Welles starring in the radio adaptation.

The airing of The Black Museum episodes presents problems for historians. Produced in 1950, it was first aired as a “pirate broadcast” by Radio Luxembourg, and then throughout Europe. It was eventually licensed by MGM Radio Attractions and ran in the United States under the Mutual Broadcasting System (MBS). MGM hand-picked what it considered to be the best 39 of the original 52 episodes and ran them from January 1, 1952 through December 30, 1952 (with a three month hiatus while a summer replacement filled the gap). This is the run from which we have taken “The Raincoat.” There’s more to the odd packaging and eventual airing of select episodes of The Black Museum (Canada’s CBC radio would also purchase some 38-39 episodes and air them at different times than the American run, for but one example), but all of that is neither here nor there for our current purposes.

Host and narrator of “The Raincoat” (as he was for the entire series), Orson Welles captivates the listener with his hypnotic voice as he relates the story of a man convicted of murdering his wife. But there is a most peculiar element making this episode unique (in the true sense of the word) and the only way to discover what makes this a most special (but true) story is by listening to the very end to find the secret of why this episode is titled simply “The Raincoat.”

Play Time: 28:54

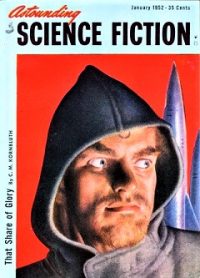

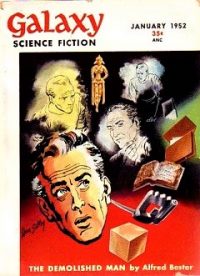

{The neighborhood gang needed more than a raincoat on their way to the corner newsstand in January of 1952. Two of their three selections were of relatively new magazines, but they also picked up a standard favorite. Astounding SF (1930-present, now Analog) ran fan favorite C. M. Kornbluth’s “Their Share of Glory,” which would become a future classic. If that wasn’t enough, the issue also sported four other stories, three of which were written by Damon Knight, Jack Vance, and Lester del Rey. Quite an issue. Astounding was a monthly in 1952. The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (1949-present) was still mixing reprint with original fiction for its 8 1952 issues. Its first three issues were bi-monthly, but with its August issue it ramped up to that of a monthly, a schedule it would maintain until 1991 when it began combining its Oct./Nov. issues for a total of 11 per year. Galaxy (1950-1980) was charting a fresh new direction with much of the SF it sought to publish, one example coming in the issue below where it ran the first of three parts of what would become one of the most famous SF novels of all time, Alfred Bester’s The Demolished Man. Galaxy was a monthly in 1952.]

[Left: Astounding, Jan. 1952 – Center: F&SF, Feb. 1952 – Right: Galaxy, Jan. 1952]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.