Tangent Online Presents:

An Interview with Lester & Judy-Lynn del Rey

(founders Del Rey Books)

Dave Truesdale

Location:

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Event & Date:

Minicon 10

April 18-20, 1975

Originally appeared in Tangent No. 3, Sept., 1975

Introduction

As was the case with the William Tenn and Donald A. Wollheim interviews reprinted here (as well as those forthcoming), the following interview was one of seven conducted at my first real science fiction convention. Lest I repeat myself, a full explanation of the circumstances surrounding this convention can be found by reading the introduction to the William Tenn interview. Suffice it to say that my friends and I had a busy weekend interviewing many of the biggest names in the field of science fiction and fantasy. In some cases we were, quite frankly, in over our heads. We had no idea there would be such a gathering of professional writers, editors, and publishers in attendance, and so had no idea for whom to prepare interview questions. Therefore, we were forced to wing it in several cases, trusting to our memories of works by several of our interviewees with whom we were less familiar than others, and our ability to play off of their answers in order to ask follow-up, unscripted questions. Actually, this worked very well, as having to listen carefully to answers (rather than merely letting them slide in one ear and out the other while looking at notes for the next question) made for a much more productive dialogue and led, in many cases, to some fascinating answers. I think the ability to think on one’s feet in such situations forced us to explore in more detail some of the answers given, and in retrospect proved fruitful. Especially since, as has been noted elsewhere, we were quite nervous at meeting—much less interviewing—this plethora of august personages in the first place, and were so fresh-faced and just naïve enough not to realize just who really we were interviewing. If we hadn’t been so utterly naïve and inexperienced I’m afraid we could have easily choked and ruined the opportunities granted us for this series of interviews.

Looking back at this particular interview, I recall less detail than some of the others conducted that weekend. It’s clear from comments made that we had already interviewed Philip Jose Farmer. Frankly, I had no idea who Judy-Lynn was, or her history in the field, or that she was a dwarf. Aside from still being able to hear their voices in my head, the only other vivid memory I have – and don’t ask me why this has stuck after all these thirty-four years – is the image of Judy-Lynn hopping up and into her chair next to Lester, and eating from a bowl of peanuts throughout the entire interview.

Lester del Rey’s full name was Ramon Felipe San Juan Mario Silvio Enrico Alvarez del Rey, although there remain questions surrounding the name (Lester’s sister claims that his real name was Leonard Knapp). He was born on June 2, 1915 and died May 10, 1993. Judy-Lynn (Benjamin) del Rey was born January 26, 1943 and died, following a stroke late in 1985, on February 20, 1986.

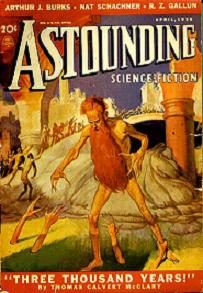

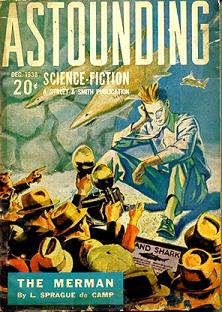

Lester’s first published story was “The Faithful” in Astounding for April of 1938 (cover at left). His most famous story, “Helen O’Loy,” saw print that same year in the December, 1938 issue of Astounding (cover at right). An accomplished short story writer during the forties and fifties, he came to further prominence in the 1950’s when writing for the Winston Science Fiction series of juvenile novels which ran from 1952 to 1961. Along with Arthur C. Clarke, Poul Anderson, Ben Bova, Donald A. Wollheim, and others writing for the popular series, Del Rey’s Winston novels include: Marooned on Mars (1952), Rocket Jockey (as by Philip St. John, 1952), Attack from Atlantis (1953), The Mysterious Planet (as by Kenneth Wright, 1953), Rockets to Nowhere (as by Philip St. John, 1954), Step to the Stars (1954), Mission to the Moon (1956), and Moon of Mutiny (1961).

Lester’s first published story was “The Faithful” in Astounding for April of 1938 (cover at left). His most famous story, “Helen O’Loy,” saw print that same year in the December, 1938 issue of Astounding (cover at right). An accomplished short story writer during the forties and fifties, he came to further prominence in the 1950’s when writing for the Winston Science Fiction series of juvenile novels which ran from 1952 to 1961. Along with Arthur C. Clarke, Poul Anderson, Ben Bova, Donald A. Wollheim, and others writing for the popular series, Del Rey’s Winston novels include: Marooned on Mars (1952), Rocket Jockey (as by Philip St. John, 1952), Attack from Atlantis (1953), The Mysterious Planet (as by Kenneth Wright, 1953), Rockets to Nowhere (as by Philip St. John, 1954), Step to the Stars (1954), Mission to the Moon (1956), and Moon of Mutiny (1961).

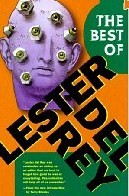

For those desiring to acquaint themselves with Del Rey’s short fiction, we highly recommend Early Del Rey (Doubleday, 1975) which features stories from 1938-1952, and The Best of Lester del Rey (Ballantine, 1978). The latter includes an introduction by Frederik Pohl. In 2000, the Del Rey Impact imprint reissued the collection as a trade paperback, with an additional introduction by Terry Brooks (cover at right). 1979 saw the Del Rey trade paperback release of Lester’s historical memoir of the field, The World of Science Fiction: 1926-1976, The History of a Subculture (cover at left). Fascinating and invaluable for anyone with a thirst for the history of science fiction and its personalities as seen through the eyes of one of its earliest, most respected, and formative practitioners and editors, it is a must-have for any serious student of the genre. In 1972 Lester began his Best SF of the Year series from Ace Books (cover of the 1972 Best SF at lower left). Lester edited the series for five years through 1976, at which time the series was turned over to, and edited by, Gardner Dozois, Ace replacing Lester due to his recruitment to Ballantine Books by its SF editor Judy-Lynn (Benjamin) del Rey.

For those desiring to acquaint themselves with Del Rey’s short fiction, we highly recommend Early Del Rey (Doubleday, 1975) which features stories from 1938-1952, and The Best of Lester del Rey (Ballantine, 1978). The latter includes an introduction by Frederik Pohl. In 2000, the Del Rey Impact imprint reissued the collection as a trade paperback, with an additional introduction by Terry Brooks (cover at right). 1979 saw the Del Rey trade paperback release of Lester’s historical memoir of the field, The World of Science Fiction: 1926-1976, The History of a Subculture (cover at left). Fascinating and invaluable for anyone with a thirst for the history of science fiction and its personalities as seen through the eyes of one of its earliest, most respected, and formative practitioners and editors, it is a must-have for any serious student of the genre. In 1972 Lester began his Best SF of the Year series from Ace Books (cover of the 1972 Best SF at lower left). Lester edited the series for five years through 1976, at which time the series was turned over to, and edited by, Gardner Dozois, Ace replacing Lester due to his recruitment to Ballantine Books by its SF editor Judy-Lynn (Benjamin) del Rey.

Judy-Lynn was a longtime fan of the genre, and began her professional career working for Galaxy magazine. Following her move to Ballantine Books, where she became its science fiction editor, she brought in Lester to edit Ballantine’s fantasy list. Due to her success in revitalizing the publisher’s SF line, she was given her own imprint in 1977 which we recognize today as the highly successful DEL REY Books imprint. Keeping in mind that the following interview took place approximately two years before the DEL REY imprint became a reality, in retrospect one can see the seeds already being sown. On the fantasy side, not only did Lester work quickly as Ballantine’s new fantasy editor, discovering Terry Brooks, but early on David Eddings and Stephen R. Donaldson as well.

Judy-Lynn was a longtime fan of the genre, and began her professional career working for Galaxy magazine. Following her move to Ballantine Books, where she became its science fiction editor, she brought in Lester to edit Ballantine’s fantasy list. Due to her success in revitalizing the publisher’s SF line, she was given her own imprint in 1977 which we recognize today as the highly successful DEL REY Books imprint. Keeping in mind that the following interview took place approximately two years before the DEL REY imprint became a reality, in retrospect one can see the seeds already being sown. On the fantasy side, not only did Lester work quickly as Ballantine’s new fantasy editor, discovering Terry Brooks, but early on David Eddings and Stephen R. Donaldson as well.

In 1972 Lester was awarded the E. E. Smith Memorial Award for Imaginative Fiction (the Skylark Award), in 1985 was honored with the Balrog Award for fantasy, and in 1990 was honored as well as SFWA’s eleventh Grand Master (following Ray Bradbury in 1988 and preceding Frederik Pohl in 1992). Harlan Ellison once remarked that he learned more about the technical craft of writing from Lester del Rey than from anyone else.

Finally, I have a confession to make. Besides the aforementioned vivid memory of Judy-Lynn eating peanuts throughout the interview, I have one other, and is where the confession comes in. I have made repeated mention in the introductions to both the William Tenn and Donald A. Wollheim interviews (as well as this one) of how naïve we were, how this was our first science fiction convention, how in awe and overwhelmed we were by it all, and how we had to wing it on occasion because we had no idea we would be conducting so many interviews and had no opportunity to properly research our impromptu subjects. I embarrassed myself only once during these interviews, and the moment came at the very first question I asked Judy-Lynn. I was mortified and more than a little embarrassed, for after I asked it I was positive that both she and Lester must think I was an idiot, and why were they wasting their valuable convention time in their hotel room being interviewed by some long-haired neofan who obviously was so ignorant of such an obvious, basic fact. I was so shamed by my error that I cut the very first question from the interview entirely. But I’m coming clean after thirty-four years. Licking my dry lips while making sure the tape recorder was ready to go, I watched as Judy-Lynn’s little hand rolled several peanuts into her mouth. I looked her straight in the eye and asked: “Judy-Lynn, what criteria do you use in selecting books for your fantasy line?” Swallowing her peanuts and without missing a beat, she replied politely: “I am the science fiction editor of Ballantine Books.” And then motioning toward Lester, “Lester is the fantasy editor.”

Hiding my embarrassment, feeling like a fool, and quashing the onrushing tsunami of panic before it could take hold and blank my mind entirely, I calmly turned to Lester and asked–

TANGENT: Lester, what criteria do you use in selecting books for your fantasy line?

LESTER DEL REY: First of all, it must be a darn good story. Second, it must have some element of magic, in the broadest sense of the word magic. Supernatural, or something related to magic. I am restricting myself from the strange, off-color fantasy thing simply because we’ve got a fantasy line which has rather deteriorated in the market, because of quaint and peculiar stories and things. We’re trying to bring it back. I’m very rigid about it. It must be a good story, it must be an interesting story.

The first story I got was a Tolkien-like story, it’s not Tolkien but it’s like Tolkien in a way. And that came as a surprise to me because I hadn’t seen a decent one since Tolkien himself. But this was a very good one. I believe it’ll be called The Sword of Shannara by a guy named Terry Brooks. It’s his first novel. Usually I find that people who write fantasy are better writers―strangely enough. Except for some who are incredibly bad. On the average they average better than those who write science fiction. But, very often, their work needs a great deal of editorial assistance to get it into what I consider to be marketable form.

TANGENT: Why do you think most fantasy writers are better than science fiction writers?

LESTER: I have found, consistently, since I began editing back in ’53 for magazines, that fantasy readers, the real dedicated fantasy readers, and writers, are amazingly literate. Much more so almost than any other group I’ve run across. I’d say that science fiction people tend to be, somewhat, more so than mystery writers. Not always, but generally. But fantasy readers―for some reason that I don’t know―are highly literate.

TANGENT: Do you agree with Lin Carter ([1930-1988] photo at right: Iguanacon, 1978 World SF Convention, Phoenix, AZ) and all of his numerous requirements for fantasy, as put forth in his book Imaginary Worlds?

TANGENT: Do you agree with Lin Carter ([1930-1988] photo at right: Iguanacon, 1978 World SF Convention, Phoenix, AZ) and all of his numerous requirements for fantasy, as put forth in his book Imaginary Worlds?

LESTER: Lin Carter and I very often get along very well―on the stories we like. But in our method of approaching it there is no resemblance whatsoever. What he says in his book is all petty technique. For instance, if I came across a book in which the names struck me as wrong, I might very well if they were awkward for the reader, as Xplqg, I would ask the writer to change those. Normally, strangely enough, a man who writes a good story has a feeling for his background so strongly his names come through almost automatically. I think that that is better done―most of the time it’s better done―by writers on a semi-conscious level, than on a fully conscious creative list of names that you should and shouldn’t do.

JUDY-LYNN DEL REY: If it works, it works.

LESTER: If I were having a fantasy laid back in Rome I’d insist that the names of the Romans were all following the Roman system. But in a purely imaginary world―well look, the names in our world are not consistent, by any means. You have names from Russian, you have names from Chinese, you have names from Indian, and everything else. And I suspect in good fantasy worlds the same would apply.

I think Lin Carter picked some very bad examples, names which I found to be ugly. So, no, I don’t pay any attention to that. I never did when I was writing and I don’t as a reader or editor.

TANGENT: What type of fantasy would you like to see? Sword & Sorcery, Tolkien-type, or something else?

LESTER: Sword & Sorcery as far as I’m concerned is a wonderful field. Now prove to me that you can do a better job of it than Howard; because Howard has already done his job. That’s the past. Now you’ve got to have even better, you can’t just have imitations. I want to see some freshness, some creativity brought to it rather than imitation, otherwise I won’t publish sword & sorcery.

Tolkien? Well, Tolkien is a broad field of the straight adaptation of ancient myth, and so on. Of course I like that. I like the idea of an adventure story; I’m particularly fond of the adventure story. I think that fantasy lends itself very well to good adventure, whether it’s swashbuckling or not doesn’t matter.

TANGENT: What about, say, the works of Leigh Brackett?

LESTER: Leigh Brackett works go very well.

JUDY-LYNN: It’s not real fantasy though, is it?

LESTER: No, but her stuff always has been fantasy, but she colors it with science fiction, which I wouldn’t want. I am trying, very hard, to eliminate all traces of science fiction from fantasy. I want the fantasy to stand as fantasy.

For example, the book I told you about earlier. The man had set up a background where this is the world 2,000 years after an atomic holocaust, where the races of Man have been changed. I liked his races of Man, but I didn’t want the atomic holocaust even mentioned. Make it into a pure neverworld, another world I told him, and let it go at that. Just leave it indefinite. The reader doesn’t need that stuff for fantasy.

TANGENT: Does your view stem from the fact that you believe fantasy should be nothing but pure entertainment?

LESTER: I think that is the basis for it. Escape? I don’t care about escape. Escape literature is something hung on it by people who sneer at something, and my god, what do they think they’re doing when they’re reading a metaphysical work many times.

TANGENT: I’m thinking about some straight science fiction that attempts to be relevant. Commentary fiction, say.

LESTER: I don’t care how much they comment on the nature of Man. Good fiction of all kinds deals in the nature of Man and naturally makes comments on it; that doesn’t bother me. All I ask is that underneath it all is a good story that will move the reader along. Not necessarily by formula stuff; I don’t want formula stuff. But something that carries an emotional tone, a measure of some kind of action which can be even mental action; some type of action that keeps the reader moving happily through the book. I want him to finish the thing and say to himself, “Ooh, that was good.” That’s what I’m after. If it has tremendous depth beyond that, fine, wonderful; the deeper a book is and can still do that then so much the better.

I wouldn’t have, for instance, published Finnegan’s Wake because it was too damned hard to read and it didn’t carry the reader along fast enough. The philosophical content of it wouldn’t necessarily throw me.

TANGENT: So, then, sword & sorcery is a pretty closed field unless someone came along who was extremely original?

LESTER: Yes. And it’s about time somebody was extremely original. There are all kinds of areas for sword and sorcery that have not been explored. Like the legend of Dys. It’s the story of the Engulfed Cathedral, a city off the coast of France which sank years ago because of the evil of its inhabitants, and there was a fantastic shadow queen there who ruled over it, controlled the shadows there, and who eventually took on a lover there who got the gates to the sea from her, opened the gates, and so forth. If you’ll examine the thing closely you’ll find there are all sorts of things for sword and sorcery there, and nobody’s touched it.

You could do a sword and sorcery against the Norse gods―not as they are―but by going back and seeing what you can do with them. There are all kinds of things you can do and nobody’s doing them. They’re doing the standard sword and sorcery with the standard barbarian who comes down with no brains―I don’t want my heroes with no brains.

TANGENT: Judy, what do you look for in the science fiction you publish?

JUDY-LYNN: Basically, I’m looking for stories…with beginnings, middles, and ends. A story that will entertain the reader, keep him interested, make him want to come back and buy more Ballantine books. I’m not interested in the purely literary works that are around, unless they have a good story. They have to have a plot.

I’ve had several writers tell me they want to raise the sights of science fiction and they’re going to educate the consumer. Well, the consumer doesn’t want to be educated, and you can’t make the consumer buy something by saying “This is good, you’ll love it.” I need to put out books that are entertaining, fun to read, and say something; not just those that say this is good for you, you’ll love it. And I’m doing a great deal of reviving in the backlist because Ballantine has a deep, wonderful, backlist; titles that have been out of print for a long time that are better than most of what’s being written today, or at least as good, they sell as well. There’s a whole new crop of readers who have never read them. And they do very well.

TANGENT: What audience should a writer write for? The lowest common denominator/consumer, or should he write up to his reader, or down, or what?

LESTER: Oh, no! He should write to please the best of himself.

JUDY LYNN: Good fiction. He should write good fiction and something he would want to read.

LESTER: One thing he should not do is show the rest of the world how wise he is, because chances are―or judging by most of the writers who want to do that―the readers are just as wise as they are, so why should they educate and uplift their readers? That’s a snotty attitude.

TANGENT: A big ego-trip, huh?

LESTER: Yes. An ego-trip.

JUDY-LYNN: These deep philosophical novels that are being turned out by students from philosophy classes, you know, it sounds terrific to them, but it’s the same old stuff to us. It’s not adding anything, it’s not telling a story, and the idea that if somebody manages to sit down and type out sixty-thousand words, and those sixty-thousand words deserve to be published―it’s ridiculous.

Books serve the function of reading and entertainment and then it can do all those other things.

TANGENT: May I risk name-dropping just so I can get a better idea of what you’re saying?

LESTER: Yes.

TANGENT: Okay, what about works such as Gene Wolfe’s “Fifth Head of Cerberus”?

LESTER: I find Wolfe so hard to read, from what I get out of it, that I never read that one.

JUDY-LYNN: Let’s drop names. Now, Delany’s new book is selling a lot of copies. I read the first thirty pages and had to quit.

TANGENT: I think it was Sturgeon who wrote that he loved it–

LESTER & JUDY-LYNN (in unison): Sturgeon likes a lot of things.

TANGENT: –and somebody else said they hated it.

JUDY-LYNN: Well, I read thirty pages and said I’ve got better ways to spend my time. I’ve met very few readers who have finished Dhalgren. And it may be the most creative, marvelous…. It’s a bleeding bore. It goes on forever.

LESTER: It’s a static book. Nothing really happens from beginning to end. Events occur, but none of them have any significance whatsoever.

JUDY-LYNN: There are enough problems in the world already; people are depressed enough. But you don’t need somebody to tell you it’s polluted outside, you can look out the window and see for yourself. You don’t need science fiction to tell you this. You don’t need science fiction to be pornographic. A lot of writers say to me, “Well, what are the taboos at Ballantine? Do you want sex or don’t you want sex?” And yes, sex, if it’s discussing attitudes towards sex in the future. If you stop the book for ten pages to do a sex scene―which science fiction writers can’t do anyway―if that’s what the readers wanted they would be reading pornography, not science fiction.

LESTER: I get annoyed at people who say it’s up to us to break the taboos, to extend the limits. Those taboos haven’t existed for I don’t know how long. I found no difficulty with those taboos back in 1950 and I don’t know what they’re talking about. They haven’t been reading much if they think those taboos are taboos now. When the mainstream has done everything already, why should you use science fiction to show how daring you are?

TANGENT: Why then, would a lot of publishers not publish Farmer’s books back then? I think he mentioned parts of Strange Relations if I’m not mistaken.

LESTER: Well, there was a time when most science fiction magazines had to depend on a double audience. It had to depend on the people who were reading it and in very many cases the parents who let them read it. But, you do owe something to your readers. If something is going to offend your readers without giving them more than sufficient reward for it, you don’t put it in. It’s not up to the editor to say, well, the reader better know about this; it’s up to the editor to publish things they will go along with. He’s got to make a living with his magazine, he’s got to please his readers. After all, in those days the reader put out 35 cents for a magazine. He’s entitled to his 35 cents worth! Otherwise it’s cheating.

And, uh, okay, in 1950 there were a number of words I would not have put in a magazine, and frankly I don’t think those words are very necessary in a story now, unless they come up bearing strong scenes where they play a significance. The throwing in of four-letter words in a story is a sign of the inability of the writer to convey his meaning without them, as a general rule. Because, even today―and there may be a time when this changes―but even today, many words do not read on paper as they sound in casual conversation. Therefore, it is not honest writing to put them in where they have a different effect.

I do admit that there are certain times when strong language, strong actions, have their point, and you put them in―now you put them in―not as a result of the way the daring science fiction writers did in the middle-sixties, but as regular writers, particularly those writing on racist problems and things like that, did in the late-forties and early-fifties. It was done by them, not by science fiction.

After all, let’s face it, to a large extent we are and always have been, pulp fiction. Pulp fiction is basically a fiction which deals with a set of timeless values. Mainstream can deal specifically with the problems of this particular narrow period and the mannerisms of this particular narrow little period. Science fiction, it’s laid in the future, and do you really believe that the language in the future is going to be precisely what it is now? Of course not. We have to get the effects, and that’s what a writer’s job is, not to report but to get the effects.

TANGENT: Would you classify such works as Dhalgren and some of Malzberg’s stuff as science fiction? And if so, isn’t there enough room in the field for such stuff, or not?

LESTER: I don’t think Dhalgren is science fiction, but that has really nothing to do with it as far as I’m concerned. There’s no development in the character, and that is a strong deficit to any book. If a character goes through a series of incidents and does not evolve as a result of them, that is a) untrue, and b) pretty silly. And when I find that that happens then I’ve got a bad book on my hands.

JUDY-LYNN: There’s a place for any fiction if people will buy it, and want to read it, but the market place is too cluttered to put out books just because somebody wrote them.

LESTER: And remember this: in the early 50’s there weren’t very many science fiction books. It was just beginning then. Most of the writers were writing for the magazines. The magazines have always had more restrictions because they go to a more general audience. In a hardcover book―well, Strange Fruit―the word “fuck” never appeared, as far as I know, since 1850, until it was used in Strange Fruit.

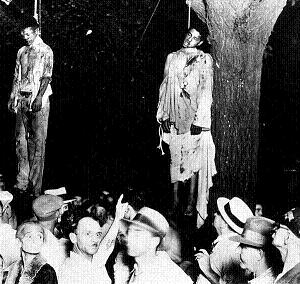

{Editor’s note, new to this first reprinting of this interview: Strange Fruit was first a 1936 poem by Abel Meeropol in reaction to the August 7, 1930 lynching of two black men — Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, in Marion, Indiana (photo at left, by Lawrence Beitler). It then became one of Billie Holliday’s iconic songs in 1939, when she incorporated it into her standard song list for her live performances–the lyrics of which were quite controversial but which Holliday insisted on including in her repertoire. The issue of racial intolerance was brought to public attention on an even more widespread basis by Lillian Eugenia Smith ( [1897-1966] photo at right) with her 1944 novel of the same name, and is the book and author to which Lester refers.}

{Editor’s note, new to this first reprinting of this interview: Strange Fruit was first a 1936 poem by Abel Meeropol in reaction to the August 7, 1930 lynching of two black men — Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, in Marion, Indiana (photo at left, by Lawrence Beitler). It then became one of Billie Holliday’s iconic songs in 1939, when she incorporated it into her standard song list for her live performances–the lyrics of which were quite controversial but which Holliday insisted on including in her repertoire. The issue of racial intolerance was brought to public attention on an even more widespread basis by Lillian Eugenia Smith ( [1897-1966] photo at right) with her 1944 novel of the same name, and is the book and author to which Lester refers.}

Okay, it was a taboo breaker. But she broke it for a very real reason and it achieved the result it should have achieved. But in the magazines of the time it would not have been proper. It would not have been what the readers were buying; in Strange Fruit they were buying a book that dealt with those things. Now, of course, in the books you can get away with almost anything. If Tom Disch wants to go and use a lot of words, or a lot of incidents in his hardcover books, then fine, but the paperback book publisher may look at it and say, not for my audience. Okay, that’s not a taboo, that’s a general audience. Which is fair and square. It would depend on the individual book; even in the magazines, also.

I would have taken from one writer a story dealing with pretty strong sex because it was intrinsic to the story and because it was handled well, and I’ve turned down a book with pretty strong sexual stuff from another writer because the sex was not really basic to the story and because it was not handled well. It was not the sex I was necessarily turning down; it was the way he presented it.

TANGENT: I see your point of course, but wouldn’t that lead to the conclusion that the audience dictates totally what is written?

LESTER: In the long run the audience does, and in the long run the audience is always right. The best part of the audience, which in the long run is what preserves books. The best part of the buying public have always determined what our great classics are. Those books, which somehow or other, over year after year after year, were not bought and read, may be occasionally taught in schools by some professor who loved them or something like that, but they are not real classics. The books that shape men’s lives over a period of years, the books that people have bought…. The book that lies sequestered in the hands of a few readers is not a book of any importance.

TANGENT: What about, say, Perry Rhodan?

LESTER: Well, uh, I didn’t say that the audience won’t buy a lot of garbage. The interesting thing though, is that for a period of time the garbage may be read, but it’s forgotten.

JUDY-LYNN: Perry Rhodan caters to a pulpy audience.

LESTER: Yeah, it’s a comic book variation.

JUDY-LYNN: It’s a juvenile type of audience, and there are people who read that. It’s not high class literature.

LESTER: You will notice that the buying public will buy books like Perry Rhodan and a lot of other books that are maybe even worse, but in the long run they discard those, they don’t influence their lives. Many of those same people will buy much better books, the books that are kept, and so on. So I have a lot of faith in the buying public. Not in its transitory, temporary buying, but in its taste.

JUDY-LYNN: When a writer is writing he is basically writing to communicate. If there’s no one out there to read what he writes or who cares what he writes, he’s writing for himself. And that is, in a sense, literary masturbation. Who cares?

LESTER: And this is the sign of a bad writer. It is the function of a writer to take his ideas and present them in a form which can be assimilated easily. That’s his job, whether he’s doing fiction or non-fiction.

the end

Lester & Judy-Lynn del Rey Interview copyright © 1975, 2009 David A. Truesdale.

Lin Carter photo copyright © 1978, 2009 David A. Truesdale.

New introduction copyright © 2009 David A. Truesdale.

All rights reserved.