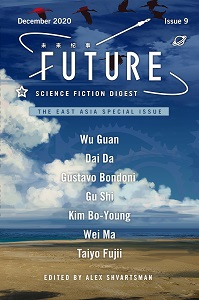

Future Science Fiction Digest #9, December 2020

#9, December 2020

“Rœsin” by Wu Guan

“Raising Mermaids” by Dai Da

“Butterfly Blue” by Gustavo Bondoni

“Reflection” by Gu Shi (reprint, not reviewed)

“Whale Snows Down” by Kim Bo-Young

“Formerly Slow” by Wei Ma

“Just Like Migratory Birds” by Taiyo Fujii

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

This issue offers fiction from authors based in China, Japan, and South Korea. In addition, an Argentinian writer provides a story set in East Asia.

“Rœsin” by Wu Guan takes place in a future world where robots have almost entirely destroyed humanity. The machines develop a passion for wearing human skins as clothing, hunting survivors for their pelts. As a form of art, one robot takes this fad to an extreme. It captures a living man, and transforms its body and actions to mimic that of the human as closely as possible. The climax leads to a change in the relationship between people and machines.

The premise is a unique one, developed in striking detail. At times, the robots seem too human, weakening the theme of the story. The narrative takes the form of a nonfiction article written by a robot, which tends to distance the reader from the events of the plot. (One interesting detail is the author’s use of unusual symbols in the original Chinese text, requiring the translator to create new pronouns and suffixes for the robot characters.)

In “Raising Mermaids” by Dai Da, an alien on Earth purchases what it believes to be a mermaid as a pet. The extraterrestrial learns that the supposed mermaid is unhappy in captivity and plans to return it to the sea. Complicating matters is the fact that the alien is undergoing the difficult process of shedding skin and molting. The struggle to reach the ocean leads to a bittersweet ending.

The author displays great imagination in the creation of a nonhuman protagonist. The narrative supplies a subtle hint as to the true nature of the alleged mermaid, requiring careful reading. The alien’s naïveté about human motives adds poignancy to the story.

“Butterfly Blue” by Gustavo Bondoni features a Mongolian astronaut. After surviving a nearly disastrous launching attempt, he receives anonymous messages warning him to have the main thruster tested. This locates the problem with the engines, preventing a second accident. While he is in orbit, he gets a request from the same source, asking him to aid a Chinese space station in serious trouble, although this requires him to go against his superiors.

With its realistic depiction of space travel, emphasis on problem solving, and disdain for bureaucracy, this story would be at home in the pages of the old Astounding. The fact that it deals with a Mongolian space program adds an exotic touch for readers in the western hemisphere, but otherwise it is a typical example of traditional hard science fiction.

The characters in “Whale Snows Down” by Kim Bo-Young are fish and other creatures living in the depths of the sea. They discuss changes in their environment, speculating that the surface world can no longer support life, explaining the unusually large amounts of organic material falling into the ocean from above.

The author vividly conveys the biology of real deep sea organisms, which are as bizarre as any aliens found in science fiction. The way in which they converse may seem overly anthropomorphic, even for fantasy. The story is an obvious warning against environmental degradation, and some readers may find its message heavy-handed.

In “Formerly Slow” by Wei Ma, privileged citizens of a nearly utopian city are subjected to technology that puts them in suspended animation for six days per week. This allows them to age more slowly than others who are not so fortunate. In addition, this system reduces the problems of overpopulation. A crisis arises when a couple have a child who cannot make use of the suspension device. Forced to stay awake each day in order to care for the infant, the couple come to have different attitudes about the technology and the city.

The premise reminds me of Philip José Farmer’s 1971 story “The Sliced-Crosswise Only-On-Tuesday World” and the series of Dayworld novels inspired by it. Although the idea is not completely original, the current tale is sufficiently different to make it more than merely an imitation. Unlike Farmer’s version, in which people are forced to live in this strange way, most of the characters in the new story are eager to use the device. The author works hard to make this seem plausible, but the reader is likely to remain skeptical.

The narrator of “Just Like Migratory Birds” by Taiyo Fujii studies the migrations of animals in artificial environments aboard a space station. The scientist receives an offer to journey to a colony world, but this will require genetic alterations resulting in entirely new physiology. In addition, it means a voyage of several years, and never returning to Earth. Because of this, it would also result in the loss of a lover, who cannot abandon the home world forever.

The plot depends heavily on the notion that all Chinese people feel an overwhelming need to return home for the Lunar New Year. (The narrator, like the author, is Japanese, so does not feel the same desire as the Chinese lover.) Although this may be a very important part of Chinese culture, it seems unlikely that even people living in deep space would make such a pilgrimage every year. The story’s resolution involves a sudden advance in technology, acting as a deus ex machina to solve the characters’ problems. The opening scene of a migrating bird in a space station is compelling, but has no relevance to the plot, other than serving as the metaphor that gives the story its title.

Victoria Silverwolf didn’t know how to put a ligature in the title of the first story, but the Kindly Editor did it for her.