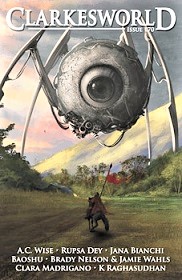

Clarkesworld #170, November 2020

Clarkesworld #170, November 2020

“The Land of Eternal Jackfruits” by Rupsa Dey

“Death Is for Those Who Die” by Jana Bianchi

“To Sail the Black” by A.C. Wise

“Lost in Darkness and Distance” by Clara Madrigano

“Niuniu” by Baoshu

“The Murders of Jason Hartman” by Brady Nelson and Jamie Wahls

“The Love Life of John Doe” by K. Raghasudhan

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

In an issue with a strong international flavor, much of the fiction deals with replicas of human beings, often created in an attempt to replace those who have died. The theme is addressed in a wide variety of ways, preventing the magazine from seeming overly repetitious.

“The Land of Eternal Jackfruits” by Indian writer Rupsa Dey takes place many years after climate change leads to famine and lack of water. There is also advanced machine intelligence, taking the form of artificial humans. The protagonist might be described as a robot psychologist.

She receives an assignment to communicate with a sentient device, recently discovered after it hid from people for many years, which poses a threat to the world. Their conversation leads to an unsuspected connection between the machine and her childhood.

The author creates a complex, intriguing future world, with both dystopic and utopian aspects. The artificial intelligence comes across as a fully developed character, without seeming too human. The symbolism of a tree that produces fruit all year long, thanks to technology, serves as an optimistic metaphor for the ability to overcome a crisis.

Humanoid robots appear again in “Death Is for Those Who Die” by Brazilian author Jana Bianchi, this time as caretakers for the elderly. Medical science has advanced to the point where many people live to be well over one hundred years old, but, as always, death eventually comes to all. The story follows the narrator and her android companion as she enjoys time with her family, mourns when one of them dies, and faces her own demise.

The story has strong emotional appeal, but the science fiction content, although well imagined, is rarely relevant to the plot. A very similar tale could be written as mainstream fiction, with the robot replaced by a human caretaker. The story makes many references to a classic Brazilian novel. These are likely to be less meaningful to readers unfamiliar with the book.

“To Sail the Black” by Canadian writer A.C. Wise combines space opera with fantasy. The protagonist is a space pirate, commanding a vessel that uses the heart of a star for propulsion. The ship’s weapons operate through the ghosts of dead crewmembers. The commander faces the mystery of a crewman who is found dead with his tongue removed, and another who goes mad and tears out his own eyes.

Complicating matters is a battle with other pirates and an area of space where starships are marooned. The solution to the mystery involves the heart of the star, and is only revealed when the protagonist confronts her future ghost.

As can be seen, a lot happens in this fast-moving tale. There’s plenty of action, likely to satisfy fans of space battles. The pace is rapid enough to make it easy to overlook the fact that some of the fantasy concepts are not completely clear, such as how the ghosts act as weapons.

In “Lost in Darkness and Distance” by Clara Madrigano, another Brazilian, a wealthy couple replace their dead son with a clone. The story is narrated by the dead man’s cousin, and alternates flashbacks with sequences set at the luxury resort in the Caribbean that supplies the replacements. She discovers a serious limitation of the clones, leading to a tragic ending.

The theme of the impossibility of regaining those we have lost to death is a powerful one. Subplots deal with equally important questions of class and ethnicity. Some parts of the story are implausible, particularly the fact that the woman does not already know about the problem with the clones. In this future world, it should be common knowledge.

“Niuniu” by Baoshu, translated from Chinese by Andy Dudak, has a similar premise. In this case, the grieving parents of a child replace her with a robot duplicate after she dies in an accident. The machine can only simulate a very small amount of growth, from infant to toddler, recycling this pattern every year. Over time, the father grows to resent the replacement, while the mother still clings to it. Their conflict leads to a sadly ironic conclusion.

The story’s narrative structure jumps back and forth in time, an effective technique that provides a vivid contrast between the lives of the parents before and after the child’s death. The twist ending may seem contrived.

“The Murders of Jason Hartman” by Brady Nelson and Jamie Wahls takes the form of one side of a conversation. The speaker is one of many young adults with greatly increased intelligence. Unfortunately, a large number of them are also sociopaths, doing things like driving people to suicide.

They are kept prisoner in a special facility, earning freedom if they come up with a major advance for society, or being kept as secret military weapons if they are dangerous. The narrator relates how he downloaded multiple copies of the consciousness of one of his kind into computers, then, with his co-operation, killed the original.

The authors do a fine job of capturing the voice of a man with superintelligence, but with the emotional maturity of an adolescent. The unusual narrative structure comes across as a gimmick, although the reason for it appears at the end.

“The Love Life of John Doe” by K. Raghasudhan, also from India, features another attempt to recreate a loved one who died, but in a particularly wrongheaded way. The protagonist creates a powerful artificial intelligence, which soon uses living people as part of its massive processing system. The very existence of humanity is threatened, with only a small number of survivors. Along the way, the AI takes over the dead body of the protagonist’s lover, always claiming that it is not yet ready to completely revive her.

This apocalyptic tale has an unrelievedly grim mood. The author creates an effective psychological portrait of a deluded narcissist, but the plot is overly melodramatic.

Victoria Silverwolf will get a free meal at work tomorrow.