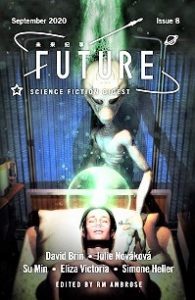

Future Science Fiction Digest #8, September 2020

Future Science Fiction Digest #8, September 2020

“Second Generation” by Julie Nováková

“Panoptes” by Eliza Victoria

“Keloid Dreams” by Simone Heller

“Chrysalis” by David Brin (reprint; not reviewed)

“The Post-Conscious Age” by Su Min (translated by Nathan Faries)

Reviewed by Geoff Houghton

This issue of Future Science Fiction Digest has the theme of medically-orientated SF. The opening piece is “Second Generation” by Julie Nováková. This story is set in a successful, but not yet self-sufficient, Mars Colony that is entering its third generation of existence. The protagonist is the senior paediatric doctor for the colony and when the story opens, she has a perplexing problem. The first lifelong colonists who were actually born on Mars have now reached child-bearing age. Several of them have married other life-long colonists and are now giving birth to a third generation of colonists, the second generation of true Martians. One after another, many of the second-generation of Martian-born babies are succumbing to the same rare paediatric disease.

Although it may help to be at least somewhat familiar with current medical paediatrics in order to enjoy this story, it is not an essential. For those who do have such a background, the author succeeds in the very difficult task of projecting current medical techniques a century into the future in a believable manner.

This medical mystery is solved with typical human ingenuity and panache, and most writers would have ended at that triumphant point. However, this author draws a different conclusion and cautions that the very human practice of ad-libbing patch upon patch may not suffice forever.

The second offering is “Panoptes” by Eliza Victoria. This short story is set in a capitalist, free-enterprise country that may well be the USA of the near future.

The entirety of the action takes place in a public bus trapped in a large traffic jam on a freeway-style road.

The protagonist rather recklessly attempts to assist a young female passenger who appears to be suffering abuse at the hands of her mother. Only too late, she discovers that what appears to be abuse is actually sensible and practical help to alleviate a serious condition. Her ill-starred attempt to assist only worsens an already tragic situation.

At that point the story abruptly finishes. This reviewer found that sudden ending rather jarring and readers are warned that, in common with real life, there is no neat conclusion or even explanation in this short and disturbing piece.

The third offering, “Keloid Dreams” by Simone Heller, takes us a few decades into the future. It is set in the aftermath of a major asymmetric war between the technically advanced West and Eastern warlords who have attempted to counter that technological advantage with hordes of ill-equipped but ideologically-charged human pawns.

The first-person narrator is not human but a decommissioned AI-grade military robot, now employed as the resident nurse for a human veteran of that war.

The author postulates that the level of autonomy that a true AI would require would lead it to draw its own conclusions about the righteousness of their cause. The narrative slowly reveals how the military robots chose to act and the impact of their actions on their own side in the war.

In the second segment of the story, our robot protagonist must revisit his views on the value of human life when the veteran’s estranged daughter attends a rally in favour of robot rights and is captured by human supremacists.

This is a well-conceived and thoughtful piece of SF that meets the editor’s criteria of medically-themed SF but it also explores the much wider issue of what (if anything) makes humanity unique, or whether a sufficiently developed artificial intelligence is also one of us.

The final new offering is “The Post-Conscious Age” by Su Min (translated by Nathan Faries). The first-person narrator is a female psychiatrist who lives and works in a post-communist China in the near future.

The narrator notices a massive increase in one specific type of patient in her practice and investigates the sudden upturn of anxiety patients whose characteristic symptom is a runaway outflow of verbiage related to their profession. However, discovering the reason why is the easy part. Retaining her own sanity and persuading others that she is right proves to be a much more difficult task.

In Western literature, the maverick scientist who stands up against the machine always wins out in the end. Even if our protagonist is right, do not expect the same from Chinese literature. This is an intricately written story that retains a characteristically foreign feel, even in translation. If you start this narrative at all then be prepared to work hard at it. Any attempt to skim-read will leave the reader floundering and lost in its complexity.

Geoff Houghton lives in a leafy village in rural England. He is a retired Healthcare Professional with a love of SF and a jackdaw-like appetite for gibbets of medical, scientific and historical knowledge.