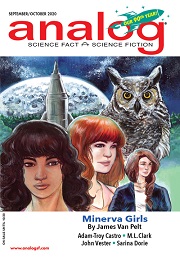

Analog, September/October 2020

Analog, September/October 2020

“Mimsy Were the Borogoves” by Lewis Padgett (reprint, not reviewed)

“Minerva Girls” by James Van Pelt

“Where There’s Life” by John J. Vester

“The Chrysalis Pool” by Sean McMullen

“A Skyful of Wings” by Aimee Ogden

“Going Small” by Jacob C. Cockcraft

“True Colors” by Beth Goder

“Drive Safely” by Stephen S. Power

“Casualties of the Quake” by Wang Yuan

“The Home of the King” by Dan Reade

“City” by Joel Richards

“Seeding the Mountain” by M. L. Clark

“The Writhing Tentacles of History” by Jay Werkheiser

“The Treasure of the Lugar Morto” by Alan Dean Foster

“Schools of Thought” by James Sallis

“The Boy Who Went to Mars” by Mary Soon Lee

“I, Bigfoot” by Sarina Dorie

“Draiken Dies” by Adam-Troy Castro

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

The magazine continues to celebrate its ninetieth anniversary with a reprinted classic from 1943, along with seventeen new stories.

The title characters in “Minerva Girls” by James Van Pelt are three middle school students. One is a mathematical genius, one is greatly skilled at putting together complex devices, and one has a father who owns a junkyard full of all kinds of equipment. After building a small submarine, they hope to combine their skills in a flight to the Moon. When two of them find out that their families are moving far away, the talented trio has to rush to complete their ambitious plan.

The author paints convincing portraits of girls in their early teens, and the story is a pleasant one. Even given the extraordinary abilities of the three, it’s very hard to suspend one’s belief when they discover a way to distort space in order to complete their mission.

“Where There’s Life” by John J. Vester consists of alternating sections told from the point of view of crustacean-like Martians and human colonists on the red planet. The pair of Martians are the last of their kind, barely surviving underground long after water disappeared from the surface of their world. The humans face their own crisis, as Earth, dealing with an approaching comet, can no longer send them supplies. Eventually the two species discover each other.

The biology of the Martians is described in convincing detail, creating unique and fascinating aliens. The humans are less interesting, and their dilemma is not very compelling. A romance between two of them seems more appropriate to adolescents than mature professionals.

In “The Chrysalis Pool” by Sean McMullen, a man sees and hears what appears to be a nymph whenever he runs by a body of water. Scientists place a device on his head to measure what happens to his brain when he experiences these seeming hallucinations. The narrator is a technician who confronts a similar imaginary being, with different results. The explanation for the phenomenon has profound implications for the human mind.

The concept is an unusual one, if somewhat difficult to understand. The characters are fully developed, and the mystery is intriguing, even if the solution is not fully satisfying.

“A Skyful of Wings” by Aimee Ogden takes place aboard a starship carrying a small human crew and multiple Earth species in frozen embryonic form to a new world. A technical problem prevents the vessel from decelerating properly, threatening the mission and the ability of the crew to return to Earth. Further crises lead to a desperate gamble for survival.

The story begins and ends with the main character’s dreams, which adds a touch of poetic imagery. The crew reacts to their situation in believable ways. The plot depends on a sister ship having the same breakdown as the first ship, which strains credibility.

“Going Small” by Jacob C. Cockcraft features a tiny spaceship carrying an artificial intelligence and a large number of human zygotes, sent to another planet as a meteor on its way to Earth is about to destroy all life. This is the entire plot of a brief story. Its main appeal is the personality of the AI, which has a wry sense of humor hiding loneliness and depression.

In “True Colors” by Beth Goder, a computerized device can provide what is claimed to be the perfect piece of art for a person, depending on reactions to other works. It produces what seems to be a meaningless result for a woman, but she discovers that there is more to it than meets the eye. Only two pages long, this is more of an anecdote than a story, with some interest as a character study and an allegorical portrayal of a certain type of personality.

“Drive Safely” by Stephen S. Power is less than five hundred words long, but it carries a powerful impact. The narrator’s automated car constantly reminds the driver of a fatal accident, attempting to gain full control of the vehicle. The ending reveals exactly what happened during the accident, and why the narrator insists on driving manually. In a very short space, the author creates a subtle tale with thoughtful implications about the nature of guilt and responsibility.

“Casualties of the Quake” by Wang Yuan, translated from Chinese by Andy Dudak, features technology that can send a man’s consciousness into an alternate version of his past. This journey to a parallel universe, and the trip home to the present, can only occur when he is close to death. The man uses the device to change what happened during a catastrophic earthquake, even though he knows this will have no effect on his own reality.

The protagonist’s yearning to save those he lost, and willingness to sacrifice himself without directly experiencing the benefit of his actions, makes for an emotionally effective story. For many Western readers, the depiction of daily life in modern China will be enlightening. One possible quibble is that the device used to travel to other universes is not very plausible.

In “The Home of the King” by Dan Reade, an aging boxer places his consciousness into a cloned version of his younger, healthier body. The narrator is a sports writer, who compares his own experiences with those of the boxer. Their conversations lead to musings on pain, symbolic death, and the bearing of one’s physical and emotional scars.

Although this is a sports story, it mostly deals with the possible social and psychological effects of advanced medical technology. Flashbacks add depth to the two main characters. The author narrates in a realistic style, and provides unusually profound philosophical speculations.

In “City” by Joel Richards, the main character lives on a Mediterranean island where, at random times, the inhabitants find themselves in slightly different versions of their previous reality. The protagonist wakes up one morning to find that he is richer, and has a servant he never knew about. He later finds out that his lover has never met him, so he begins a new relationship with her.

Written in second person, the story has a languid, decadent, fin de siècle mood. Nothing very dramatic happens, so the reader’s enjoyment will depend on whether the author’s style seems elegant or pretentious.

“Seeding the Mountain” by M. L. Clark takes place in Colombia in the near future. The main characters work to repair damage done by illegal mining that led to deadly landslides. In addition to technical and bureaucratic problems, they have to deal with an indigenous landowner who refuses to have them work on his property, the disappearance of a young assistant and his pregnant girlfriend, and unauthorized activities meant to help, which could cause harm instead.

This brief synopsis offers only a hint of what goes on in a very complex story. The author creates a richly imagined future, believable in every detail. Many readers unfamiliar with the setting will learn a great deal about the past, present, and future of a nation facing many challenges.

All of the characters in “The Writhing Tentacles of History” by Jay Werkheiser are intelligent cephalopods living in the far future, evolved from modern animals long after humans went extinct. One is a scientist who discovers an anomalous fossil. His rival contends that he is investigating an area of no importance. They present their cases to those who control scientific activities. The result of this hearing is literally a matter of life or death for the scientist.

The author manages to make the characters seem truly alien, while allowing the reader to empathize with them. The way that civilized, technological, octopus-like beings might live is presented in a completely convincing manner.

In “The Treasure of the Lugar Morto” by Alan Dean Foster, two explorers seek a valuable prize buried in a desert wasteland. What they find, and how they react to it, reveals something about the future world in which they live.

The effect of this story depends entirely on the revelations near the ending. Although not intended to be humorous, the final sentence comes across as something of a punchline. The author has an important point to make, which may be more worthy of note than the form in which it is presented.

“Schools of Thought” by James Sallis is a very short tale in which a married couple brings their misbehaving son to a psychiatrist. The doctor and the child share a common view of most of humanity, leading to an enigmatic ending. This is an intriguing, but frustratingly opaque little story.

The title of “The Boy Who Went to Mars” by Mary Soon Lee aptly describes its basic plot. The narrator’s father left his mother before he was born. Years later, as the leader of an expedition to settle the red planet, the father invites the boy to join him. His mother allows him to leave her forever, for a reason not revealed until later. The boy goes on to start his own far-reaching project.

The characters are appealing, and the colonization of Mars is presented in an interesting way. Otherwise, this is a very simple story, without much to distinguish it from similar works.

“I, Bigfoot” by Sarina Dorie is narrated by, as one would expect, a Sasquatch. He makes a dangerous journey to a city, where he rescues a runaway child from thugs. He escorts her back to her home. In exchange, she gives him a backpack full of provisions for his kind. Their encounter leads to conflict within his tribe, and a change in the way they deal with people.

With its young human protagonist and light mood, this story reads like young adult fiction. Even if one accepts the existence of a Sasquatch, it is hard to believe that he would learn to read English by studying scavenged magazines.

“Draiken Dies” by Adam-Troy Castro is the latest in a series of stories about two enhanced warriors and their battles against a criminal organization. This one begins with one of them captured and rendered helpless by the villains. Monitors reveal any attempt at lying, so she must tell them the exact truth, including the surprising fact that she killed her partner, at his request. Flashbacks reveal how she arrived on a dismal planet, rescued a teenage girl from her abuser, and wound up captured by the criminals. Although she tells them nothing that is false, they do not realize the full implication of what she says.

The plot contains enough violent action to satisfy any reader looking for exciting adventure fiction. The woman is so incredibly powerful that she seems like a comic book superhero. The way in which she uses complete honesty to deceive her captors is clever, but readers may feel cheated by some of the ways they are misled as well.

Victoria Silverwolf would like to point out that “Lewis Padgett” is actually a pseudonym for the married writing team of C. L. Moore and Henry Kuttner, and that the story reprinted in this issue is only one of their many excellent works.