“The Panchinko Gambit” by Chris Edwards

“The Thrallcatcher’s Apprentice” by Deborah A. Wolf

“The Road to Hella” by Ben Galley

Reviewed by Tara Grímravn

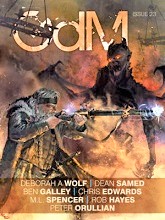

Grimdark is back this month with its 23rd quarterly issue featuring three brand new stories. Readers will quickly note that this trilogy of tales is united by a single common thread—slavery. While that word may initially evoke thoughts of a certain period in American history, that’s not quite what audiences will find here. Make no mistake—slavery can take many forms, as we’ll soon see.

“The Panchinko Gambit” by Chris Edwards

At some point in the recent past, Andy was charged with homosexuality and sentenced to spend the rest of his life as a Salvationary, a sentence that is virtually guaranteed to end in a gruesome death as a suicide-soldier-for-hire. Stationed in Japan and under the watchful eye of their commander, the not-so-pleasant Chaplain Williams, Andy’s group is wakened in the middle of the night by an alarm alerting them of incoming Chinese attack forces. The problem is they don’t know exactly what they’re dealing with and are likely very much underequipped to be able to survive the coming mission.

Edwards’s story provides a pretty bleak peek at what would happen if religious fundamentalism were to take over the United States, even though the story is set in Japan. It quickly catches the reader up in a sense of unease and frighteningly fanatical religious control. That said, I did have to wonder how this came to be if no one really believed the religious teachings except a crazy few.

Some of the dialogue between Andy and TB seems a bit off, as well. For example, their conversation on entering the pachinko parlor seems a little too convenient for the reader. Granted, the purpose is to give some background to the two characters, but they’d already been Salvationaries in the same groupo together for some time—they weren’t suddenly thrown in the mix with each other and needing to introduce themselves. Since Andy tells us what crimes each of them was imprisoned for earlier (except, of course, for TB who he says won’t share), how did Andy’s job as a conflict accountant never come up in the past? That seems like something that would have been a topic over one of the many card games they mention playing together. As a result, it just seems a little too out of place at this point in the story, and I have to admit that it did knock me out of the narrative enough to go back and re-read the portion where Andy divulges why everyone was in the Salvationaries in the first place.

Those few little quibbles aside, it’s a solid piece. It’s action-packed, fast-paced, and certainly imaginative. Humor in so dark a tale can be hard to pull off, but Edwards does a great job at including it in just the right spots to lighten what would be an otherwise very heavy story, even with the rather lighthearted ending and absurd mission objective.

“The Thrallcatcher’s Apprentice” by Deborah A. Wolf

Jenn, born a member of the Tachak tribe, had been kidnapped by the empire at four years old before being sold into the service of Master Rohnen, who has been training him as a thrallcatcher. Now in his teens, if he ever hopes to regain his freedom, he must prove he’s capable of being skillful, brave, and able to complete enough hunts so he can pay off his soul debt and the fees for his upkeep and training. Tonight, he finds himself at the edge of an elder wilderwood with two other thrallcatcher trainees searching for an escaped thrall. But Toska Forest is rumored to be a frightening place, and there’s no telling what they’ll find within its shadows.

To start with, I honestly enjoyed Wolf’s story. In fact, I was genuinely eager to read it through to the end. Even though the reader only gets to see a tiny glimpse of it here, the world she’s built is fascinating and I’d love to read more stories set within it. Jenn is a great character and I can easily see him in the starring role in more stories. And I have to say that Wolf has cooked up one hell of a satisfying ending.

The only point of contention I found in Wolf’s tale is on the topic of soul debt. It’s a fascinating concept and mentioned consistently throughout the narrative. It’s also the source of the servitude to which all of Jenn’s people are subjected, so what is it exactly? I’d have liked to understand why the Tachak people owe a soul debt to the empire from before birth. My guess is that it has something to do with the subjugation of the Tachak by the Kochevian Empire but it’s never mentioned. This would have helped to flesh out the story. Other than that, this is a fantastic read.

“The Road to Hella” by Ben Galley

Lorn Bar-Koran has been traveling for years. His road is finally nearing its end, having now led him to a near-empty tavern called The Gilded Griffin. Once inside, he is met with a less-than-warm welcome. After being questioned by the tavern’s few suspicious customers, Lorn reveals that he’s a bounty hunter searching for his quarry, prompting a tense confrontation. The old hunter, however, quickly shuts the men down by flashing the mage-gun hidden in his garments, which sends them scurrying out the door. Secure in the knowledge that his quarry is near, Lorn strikes up a conversation with the innkeeper, eager to swap tales before he claims his next bounty.

I honestly must admit to feeling a bit torn on this story. As a writer and reader, it is for the most part an enjoyable ride (although the typos could have been edited out a bit better). When I first read the title, I was incredibly excited to get into it and, for the most part, the narrative sustained my excitement. Unfortunately, cracks started to show near the middle of the story.

It took getting to Lorn’s story to see that the premise is loosely based on the Norse myth of Baldur’s murder combined with that of the Greek tale of Orpheus and Eurydice. If it weren’t for the ending, I could have overlooked that particular lack of originality along with the tropey cliché of death being personified as a treacherous villain, especially since it is a somewhat (though just barely) accurate description of the Norse goddess Hel. She was greedy, cruel, and indifferent to mortal plights—and those first two epithets certainly describe Galley’s Hella; not so much the third, though. Unlike her father Loki, Hel wasn’t exactly portrayed as treacherous in the admittedly sparse descriptions of her in surviving mythology. Of course, this is all part of artistic license and the author’s interpretation of myth for the needs of his story, and I can accept that. Hella’s character, however, remains an integral part of why the plot falls apart at the end.

The theme of Galley’s story falls along the lines of “be careful what you wish for.” When Lorn first speaks with Hella, she specifically states that if he delivers a thousand souls to her, he “shall be with [his] wife again.” He, for his part, makes it quite clear that his entire purpose was to be reunited with Cataea. It’s the same request Orpheus makes of Hades (or Hecate, depending on the source) and that Hermod makes of Hel on the gods’ behalf. But in the end, when Hella reappears to claim the last soul, she says that he never specified his own fate. That is what kicked me out of the story. I had to go back and re-read their previous exchange, only to find that something about this bait-and-switch did not add up. Not only is this “twist” that Hella tosses into their deal incredibly run-of-the-mill to the point of being predictable and boring, it just doesn’t follow what they had agreed upon earlier. Had the initial conversation been vaguer on Lorn’s part, this could work but, as written, it feels conveniently thrown in for the sole sake of upping the stakes for Lorn.

Could it be argued that perhaps Lorn is an unreliable narrator and therefore misremembering his bargain after all these years? I don’t believe so. That device is a first-person viewpoint technique, for starters. The reader is also not given any indication that Lorn’s mind has slipped, regardless of how tired and bedraggled he feels after years of hunting criminals. Neither he nor the viewpoint fit the literary definition of an unreliable narrator, so there’s no reason to think that he’s somehow incorrect.

All in all, this isn’t by any means a terrible story. It’s worth a read, to be sure, but it has, in my opinion, at least one serious fault and a few others that are minor in comparison (the name of the demon servitor, for one, regardless of whether one considers the 17th-century manuscript The Lesser Key of Solomon to be a work of fiction—albeit an obscure one, at least to the mainstream—or not).

Grimdark

Grimdark