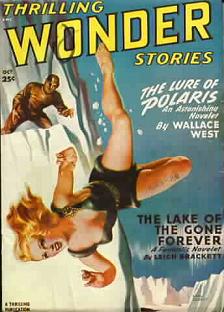

This touching, sensitively rendered adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s (1920– ) classic short story “Kaleidoscope” aired on Suspense on July 12, 1955. It first saw print in the October, 1949 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories (cover below left; which also included stories by, among others, L. Sprague de Camp, Leigh Brackett {“The Lake of the Gone Forever”}, Henry Kuttner, Margaret St. Clair, Manly Wade Wellman, and L. Ron Hubbard).

This touching, sensitively rendered adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s (1920– ) classic short story “Kaleidoscope” aired on Suspense on July 12, 1955. It first saw print in the October, 1949 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories (cover below left; which also included stories by, among others, L. Sprague de Camp, Leigh Brackett {“The Lake of the Gone Forever”}, Henry Kuttner, Margaret St. Clair, Manly Wade Wellman, and L. Ron Hubbard).

A brief bit of backstory concerning “Kaleidoscope” first. A few facts, quotes, and context never hurts and often helps in reader, or in this case, listener enjoyment or appreciation.

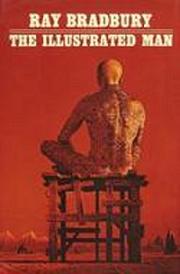

Book publisher Doubleday put together a linked series of eighteen Bradbury stories in hardcover in February of 1951 titled The Illustrated Man. (Said title had sold one million copies in hardcover and numerous paperback reprintings as far back as 1969–that’s as of forty years ago, and the title has been in countless editions, and reprintings, since.)

The strikingly beautiful and lifelike “tattoos” (or, as Rod Steiger, playing the title role in the 1969 movie calls them–skin illustrations–as per the story) covering the entire body of the title character, when stared at, come magically to life in the eyes of the viewer, revealing strange and startling stories–all from the future. The hapless, despondent “illustrated man” has been searching for fifty years for the enigmatic time-traveling “witch” from the future who had set up an innocuous little tattoo parlor where he had spent one long-ago night getting his benign (or so he believed) tattoos. As Bradbury writes in his Prologue (the framing device for the diverse stories included in The Illustrated Man):

The strikingly beautiful and lifelike “tattoos” (or, as Rod Steiger, playing the title role in the 1969 movie calls them–skin illustrations–as per the story) covering the entire body of the title character, when stared at, come magically to life in the eyes of the viewer, revealing strange and startling stories–all from the future. The hapless, despondent “illustrated man” has been searching for fifty years for the enigmatic time-traveling “witch” from the future who had set up an innocuous little tattoo parlor where he had spent one long-ago night getting his benign (or so he believed) tattoos. As Bradbury writes in his Prologue (the framing device for the diverse stories included in The Illustrated Man):

” ‘In 1900, when I was twenty years old and working a carnival, I broke my leg. It laid me up; I had to do something to keep my hand in, so I decided to get tattooed.’

‘But who tattooed you? What happened to the artist?’

‘She went back to the future,’ he said. ‘I mean it. She was an old woman in a little house in the middle of Wisconsin here somewhere not far from this place. A little old witch who looked a thousand years old one moment and twenty years old the next, but she said she could travel in time. I laughed. Now, I know better.’ … ‘I’ve hunted every summer for fifty years,’ he said, putting his hands out on the air. ‘When I find that witch I’m going to kill her.’ “

As the Illustrated Man’s overnight, roadside traveling companion, just met, observes: “As for the rest of him, I cannot say how I sat and stared, for he was a riot of rockets and fountains and people, in such intricate detail and color that you could hear the voices murmuring small and muted, from the crowds that inhabited his body. When his flesh twitched, the tiny mouths flickered, the tiny green-and-gold eyes winked, the tiny pink hands gestured. There were yellow meadows and blue rivers and mountains and stars and suns and planets spread in a Milky Way across his chest.”

The lead story in this iconic, landmark work is another classic Bradbury short story familiar to all, save perhaps those coming new to Bradbury for the first time, “The Veldt” (which, if you think about it, presages and surpasses any of the computer-generated Virtual Reality stories of today by light years). The second story, as the friendly traveling companion gazes entranced at another tattoo, at his next glimpse of the future as it slowly shimmers, wavers, comes to life, then coalesces to a future reality on the very skin of the Illustrated Man, and is again more real than any virtual reality experience, is “Kaleidoscope.”

The lead story in this iconic, landmark work is another classic Bradbury short story familiar to all, save perhaps those coming new to Bradbury for the first time, “The Veldt” (which, if you think about it, presages and surpasses any of the computer-generated Virtual Reality stories of today by light years). The second story, as the friendly traveling companion gazes entranced at another tattoo, at his next glimpse of the future as it slowly shimmers, wavers, comes to life, then coalesces to a future reality on the very skin of the Illustrated Man, and is again more real than any virtual reality experience, is “Kaleidoscope.”

A number of other Bradbury stories from The Illustrated Man were dramatized for radio, among them “Marionettes, Inc.,” the aforementioned “The Veldt,” and one of the most oft-dramatized of all SF stories on Old Time Radio, “Zero Hour.”

Suspense was one of Old Time Radio’s longest running thriller shows (1942-1962), and justly deserves the accolade of a “classic” radio show. It maintained high production values and drew some of Hollywood’s greatest directors and actors over its twenty-year run, including Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, Gene Kelly, Susan Hayward, Jimmy Stewart, and Cary Grant (who once remarked: “If I ever do any more radio work, I want to do it on Suspense, where I get a good chance to act.”). Bernard Hermann, who early-on worked with Orson Welles in his Mercury Theater series (and who would go on to work with Hitchcock in films), composed many of the musical scores for Suspense. The show was billed as “radio’s outstanding theater of thrills,” and listeners soon came to anxiously await the show’s introduction, which included the signature line, “We invite you to enjoy stories that keep you in …. SUSPENSE!”

While America listened to “Kaleidoscope” in the summer of 1955, SF fans were reading stories such as Eric Frank Russell’s 1955 Hugo winning short story “Allamagoosa” (Astounding Science Fiction, May), and Charles Beaumont’s short story “The Vanishing American” (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, August). A few of the notable SF novels to appear in 1955 include Solar Lottery by Philip K. Dick, Earthman, Come Home by James Blish (the first published, but the third chronologically of the four titles in his classic Cities in Flight novels), and The Long Tomorrow by Leigh Brackett, one of Ray Bradbury’s closest, dearest friends, and mentors.

[As a personal observation only, and for those who know their SF history, I put forth the proposition that Ray Bradbury’s 1949 short story “Kaleidoscope” is an obvious precursor in general theme (if not scope) to the more famous and justly acclaimed Sir Arthur C. Clarke 1955 short story “The Star,” from the November issue of Infinity Science Fiction (first issue 1955, last issue 1958). Clarke’s “The Star” nailed “it,” dead on, and deserves its rightful place as one of the most famous science fiction short stories of all time. But Bradbury, six years earlier, almost to the month, and on a much smaller scale–focusing as it does on the more personal, human element–nailed “it” just as assuredly.

Clarke’s story envisions a dying sun (a supernova) from far, far away as viewed from Earth at the time of the birth of Christ, with its world-wide religious impact here on Earth. The final line of the story is iconic, one of a kind, a classic and unforgettable, and effective for its world-wide, historical, scope. It just doesn’t get any better, at least from a non-religious perspective.

Bradbury’s story envisions a dying astronaut (flaming out on re-entry, appearing like a bright star to those on Earth who happen to see it) with an individual, human, impact on an innocent child, full of wonder, who is gazing at the night sky and imagining what it might be. The last line is also memorable and touching and no less effective for its smaller, individual scale. Religious implications are non-existent.

Both stories, to all intents and purposes, have extraordinarily bright “stars” in the sky with unexpected, yet life-changing consequences on different levels. And oddly enough, and in their own way, both center around young children.]

Set aside, if you please, a few quiet minutes (whenever you can find them) to enjoy Ray Bradbury’s poignant short story “Kaleidoscope,” this sad but quietly uplifting human tale, superbly adapted for radio, well known to those familiar with Old Time Radio, and an OTR SF classic.

Play time: 23:32