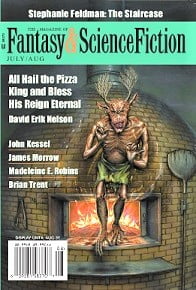

Fantasy & Science Fiction, July/ August 2020

Fantasy & Science Fiction, July/ August 2020

“Knock, Knock Said the Ship” by Rati Mehrotra

“Last Night at the Fair” by M. Rickert

“Bible Stories for Adults No. 37: The Jawbone” by James Morrow

“Spirit Level” by John Kessel

“All Hail the Pizza King and Bless His Reign Eternal” by David Erik Nelson

“Madre Nuestra, Que Estás en Maracaibo” by Ana Hurtado

“A Bridge from Sea to Sky” by Bennett North

“Crawfather” by Mel Kassel

“Omonculus” by Madeleine Robins

“The Staircase” by Stephanie Feldman

“The Monsters of Olympus Mons” by Brian Trent

“The Shape of Gifts” by Natalia Theodoridou

Reviewed by Seraph

“Knock, Knock Said the Ship” by Rati Mehrotra

In such divisive times, stories about the meaning of friendship and family seem ever more relevant. This particular story is set aboard an aging medical vessel now converted into a trading ship, its crew hauling cargo for thin profit margins just to survive an existence scarred by loss and war. As pirates pretending to be security forces invade the ship, Mehrotra peers deep into the future, long since humanity has taken to the stars and colonized our solar system. It is unsurprising how little some things change, good and bad. One of the crew of the medical ship finds an unexpected kinship with the murderous intruders, and is drawn back to the tragedies that claimed her home and her childhood. Much of the story follows her insight into their motives, her efforts to stop them, and the lengths to which she goes in order to help the survivors of her settlement that the pirates were trying to feed and supply. The ending is heartwarming, and it’s interesting to see how close a friendship can form between an AI and a human, as well as just how important family can be, especially when so few remain.

“Last Night at the Fair” by M. Rickert

There will always be a place for fairy tales, whether of the original darker variety or of the new more heartwarming kind. This falls definitively into the latter. Set in a small town in recent times, it begins during the childhood of the narrator (one Anne-Marie), at a traveling fair. She reminisces about a number of things across the span of her life and marriage, which just happens to be to the boy she went to the fair with all those years past. There is nothing sinister in this telling, nothing but love, good memories, and a beautiful ending. There is something of a supernatural or mystical twist throughout, though nothing truly definitive, and it only serves to heighten the beauty of it all. The present time of the story is after her husband has passed, but there is no sad ending here: at the end she is reunited with him, in nothing short of spectacular fashion. This was the bright spot of the entire issue, and I highly recommend the read.

“Bible Stories for Adults No. 37: The Jawbone” by James Morrow

This story had genuinely significant potential, and it’s all the more crushing for how much that potential is wasted. A creative retelling of the story of Samson and Delilah, it is set in Israel and Philistia during the pre-Scattering era of the Judges in biblical history, told from the point of view of the Angel of Death. Even notwithstanding the inexplicable modernistic need to rewrite any male figure (tragic, heroic, or otherwise) as a hapless brute capable of naught but senseless violence, the twist of Delilah’s love for Samson driving her treachery was set up for greatness. Samson isn’t exactly a paragon of virtue even in the biblical account, and his tale is already far more cautionary than heroic, so recasting him as a hapless brute isn’t nearly as much of a stretch as other such retellings have attempted. The stroke of Delilah’s only desire being to see his true potential as a man of peace and justice was masterful, as it hits home to the core of his greatest failing: given powerful gifts and a divine purpose, he squanders both, like Esau before him. And then the writer bizarrely decides to just abandon all illusion of potential in order to pontificate grandiosely about a specific set of modern political issues that have absolutely nothing to do with the story. The latter half of the story is more reminiscent of an acid trip than actual fiction, and the smugness that drips from the page is like pouring rancid vinegar on fresh pastries and calling it icing.

“Spirit Level” by John Kessel

This was almost more a work of horror than fiction, but it was played out well and written equally well. The pacing was just slow enough that you didn’t feel rushed to the end, but you could appreciate each step along the way. The story follows an aging man haunted by the ghosts of his past in a literal sense, albeit several of those ghosts aren’t actually dead and exist primarily in his guilt-ridden mind. Not that this stops them from injuring him both emotionally and physically. The setting could be any modern urban center, mostly of the white-collar office variety, and the timeline is clearly sometime recent or present, though the concepts within are timeless. This is an excellent essay on mental anguish and depression, and the toll it takes on not only the sufferer but all those around. It makes especially good note of how depression sucks the joy out of even the most primal enjoyments in life. It doesn’t shy away from the all-too-common way these things tend to end, so if suicide is a difficult topic for you, be warned. It isn’t handled indelicately, quite the opposite, and the author deserves some credit for that.

“All Hail the Pizza King and Bless His Reign Eternal” by David Erik Nelson

If the preceding fairy tale was beautiful and innocent, this fairy tale is anything… perhaps everything but. In every way that it can be, it is sinister, twisted, convoluted and entirely well played. Set in and around a pizzeria by the name of Kip’s Taco Burger on Michigan Ave, I couldn’t place the time frame but it is clearly modern enough. On a craving, one of our characters by the name of Melissa heads to Kip’s at exactly the wrong time, and ends up eating something unexpected. In a very bad variation on the “what’s in your taco meat?” joke, it is revealed that soon after her fateful meal, Kip is arrested for killing his wife, carving her into pieces. and grinding her up into the meat that went into Melissa’s food, all at the supposed orders of the Devil. When Melissa’s step-sister Shelly buys up the place many years later, Melissa tries to warn her but walks into far more than she bargained for. The “Pizza King” does not refer to Kip so much as the demon who is trying to open a gate to Hell through the earthen bricks of the pizza oven, and it doesn’t get any less weird from there. In the world of oddity, this story fits in wonderfully, and should appeal to fans of the wickedly weird.

“Madre Nuestra, Que Estás en Maracaibo” by Ana Hurtado

Horror isn’t all screams and things jumping out of the dark with intense noise. The best horror is slow, methodical, and most importantly inevitable. As John Wick is so fond of dourly saying, “Consequences.” Said consequences don’t need to be obvious, and don’t need to announce themselves in a way that’s easy to understand, but in the end, it needs to make sense why it all went wrong. Juana, Yesenia’s grandmother, prays to the dead, and that’s when it all starts. The dead come for her before her time, but that’s not where it ends. Thanks to some quick thinking and some definitive action from Yesenia, the spirits trying to prematurely claim her abuela’s life are repelled, and she peacefully passes two weeks later. As to a time frame, I was left unsure, but I can say it takes place in Maracaibo, Venezuela, and that it certainly borders on the macabre. As you read through the story, it isn’t always obvious quite how you’ll get there, but the ending is much less frightening than the climax would indicate.

“A Bridge from Sea to Sky” by Bennett North

When describing a setting, how often do you get to say that it literally occurs between heaven and earth? This science fiction story is set a good ways into the future and revolves around the cable for an orbital elevator. When the cable gets damaged during a routine maintenance mission, the shaken and injured crew sets out to figure out the damage and report back to command. When the damage turns out to have all but severed the massive cable, we are treated to a fairly complex and intricate set of interactions between all of the different agencies and countries involved in funding the orbital elevator. There aren’t a lot of people who live at the top, but the station that the elevator leads to was of major significance in allowing humanity to expand beyond the Earth’s surface. When the workers discover that the bean counters down below are going to decommission the elevator, they take a brave and courageous stand for their home. There isn’t a whole lot about this story that makes it stand out, but it is plenty enjoyable nonetheless.

“Crawfather” by Mel Kassel

It is somewhat difficult to discern the time and place in this tale of cyclical loss and vengeance, although in a general sense Bluegill lake could be in any of dozens of lowland areas known to host crawfish, and there is nothing to suggest a time frame too the far past or future. On the surface, this is a fairly simple tale in the styling of the Loch Ness monster tales, with a hint of Ahab’s obsessive combativeness, albeit with an entire extended family rather than a single bitter old sailor. The twist at the end is short, sweet, and understated, although deeply sinister in its implications. And really, all you get is the single implication. The battle against the monstrous daddy of all crawfish doesn’t go particularly well, but when a couple of furious younger members of the family slay the great beast with very little effort not everything goes as it should. All in all, the story doesn’t stand out in any way, but it is plenty entertaining all the same, and the twist at the end gives it just enough punch to make you think about it after you’re done.

“Omonculus” by Madeleine Robins

Another creative retelling, but this time My Fair Lady is the target of revision, with a futuristic steampunk twist. This retelling is much better executed, and is actually very well written. It takes place in London, just as the original, but this time around it is a specifically constructed automaton that is the subject of Monsieur Higgin’s attentions rather than a young lady from the streets. The automaton is designed simply to speak, although quickly you learn how not simple such a task is for a programmed mind. In the process, Eliza (as the automaton is named, of course) learns much more than how to speak, and by the end has quite suitably surpassed her erstwhile mentor, thoroughly humiliating and discrediting him in the process. The original near-inexplicably has Eliza re-uniting with the repugnant Higgins with seeming little consequence for his treatment of her, and not even an apology to mollify her. This retelling has her not only learning to speak, learning to learn, but most of all learning to live… something she accomplishes quite well and with admirable success.

“The Staircase” by Stephanie Feldman

This story is lighter than some of the other stories in this issue, a kind of coming of age story for a group of teenage schoolgirls. The emphasis is more on the horror side of the spectrum, but is every bit as much about the interactions and friendships among the girls as it is the scarier stuff. No location is given beyond “our town” but the most important location in the story is a staircase cut into the side of a grassy hill. The dark, mysterious staircase has taken on mythological status with the locals, and the truth behind the myth resembles something of a cross between an evil pied piper variant and the slender man myth. One by one the girls are drawn into the shadow, claimed by the figure who resides across the veil until only one remains. When he comes for her, she manages to resist and fight him off through sheer force of will, but it comes at a tremendous cost. True, his spell is broken over all of them, and they seem to not only have forgotten the entire ordeal, but be physically restored as well. However, the bonds that bound them together are shattered, much to our heroine’s dismay. There is nothing truly surprising or unique beyond the nature of the creature who lives down the staircase, but it’s well executed and enjoyable as a story.

“The Monsters of Olympus Mons” by Brian Trent

Far into the future, long after humans have colonized Mars and long after an insurrection to establish its independence resulted in a tyrannical Partisan government, an old man seeks the help of three ghosts to right an ancient wrong. Three AI constructs based off the personalities of three dead museum curators killed for helping wounded insurgents find themselves carrying the torch of a famous climber often used as propaganda for the vicious Martian regime. All he wants as he takes his last breath is to take down the flag he planted at the top of Olympus Mons, but the path is not as simple as just reaching the peak. The Partisan Special Ops stand in the way, the same ones who killed the poor old man as he tried to scale the peak. The full treachery and fascism of the totalitarian regime are on display, as the commander of the SpecOps does everything in his power to prevent their effort. The courage of the ghosts is beyond question, and eventually they succeed, although suffering the ultimate cost. The themes seem ever more relevant in current times, but all that aside, it is still a wonderfully constructed tale, and full of meaningful commentary.

“The Shape of Gifts” by Natalia Theodoridou

This final story was by far the most mystical of all the offerings in this issue, and not the least strange of them, either. Parts of this story resonated with me, and while it meanders frequently, it has threads of long past lives, ancient gods, and rebirth that fascinated me. Set (mostly) in a cabin out in the wilderness, it follows the experiences and life of the narrator, an extremely complex individual, and the woman who ends up in the role of lover. Both seem to be conservationists, tracking endangered birds and other creatures, but our narrator is not entirely human. The time frame reflects this, as it takes place in a more modern era, but traces back to something else. Something different, something older and more primal. There is plenty of romance, mystery and perhaps even love. There is certainly joy, as well as loss. The ending is utterly predictable, but the journey here is the more important part. I hesitate to say that it is well written, as it meanders considerably and stops and starts abruptly at times, but it is not poorly written at all, either. I can see that it has potential, even though parts of it felt disjointed and others fell flat.