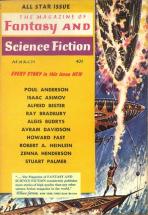

This month marks the centennial of science fiction grand master Robert A. Heinlein‘s birth, and it would seem inappropriate not to somehow acknowledge that here in Tangent‘s “classics” corner. Given that the event currently being commemorated is a birth, a Heinlein story about a birth seems right, and the obvious pick there is his short story “All You Zombies—,” which first appeared in the March 1959 issue of the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

This month marks the centennial of science fiction grand master Robert A. Heinlein‘s birth, and it would seem inappropriate not to somehow acknowledge that here in Tangent‘s “classics” corner. Given that the event currently being commemorated is a birth, a Heinlein story about a birth seems right, and the obvious pick there is his short story “All You Zombies—,” which first appeared in the March 1959 issue of the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.You might find, however, that putting all the pieces together yourself can be the source of a lot of the fun (this certainly seemed to be what interested my students most when I used the story in my classes), and in any case, that dizzying intricacy imparts to the story much of its appealingly zany quality—though as is so often the case with stories that go this far over the top, there is a Big Idea here. “Zombies” is not only about the paradoxes time travel might introduce into our histories, but the cosmic aloneness that comes with just maybe being the only thing in the whole universe—a common theme in Heinlein’s writing and interestingly enough, one frequently at the center of Heinlein’s time loop stories. Where John Connor in The Terminator and Marty McFly in Back to the Future ended up using time travel to make sure they were born, Heinlein tended to go further, making sure that he conceived himself—sometimes, with himself. As H. Bruce Franklin put it, “The narrator is the ultimate self-made man, the logical end point of the epoch based on the belief that ‘I think, therefore I am.'”

Sometimes the prospect of solipsism is presented as seductive, like in 1973’s Time Enough For Love, when the unbelievably self-absorbed Lazarus Long, after having had sex with twin adolescent female clones of himself and botching his own attempt to make love to a mother he finds irresistible because she seems like a mirror image of himself, hears the Gray Voice tell him that it was all him, all along. At other times, it is nightmare rather than dream, though in either case, generally untenable, play for angels at best (as in Stranger in a Strange Land), an existential trap at worst.

Interestingly enough, technology’s potential to realize solipsistic fantasy has gone even further with the idea that the human mind can be uploaded into a computer where, it is often supposed, the digital version of the mind can control every aspect of its environment, a universe unto itself. While it is now decades old (I recall seeing it crop up, in among other places, Philip Jose Farmer‘s brilliant The Unreasoning Mask), the pop futurism of writers like Ray Kurzweil has made it much more popular in recent years, and much more likely to be depicted as a part of everyday life in the near future, a noteworthy recent example being Carlos Hernandez‘s “Exvisible” in the July 2007 issue of Interzone. Whether this is a response to the changing frontiers of technological possibility, or a sign of some deeper psychological change—perhaps a move away from a concern with being self-made, to a mindset with a more flexible view of the prospects for remaking the world (or less grandly, just where our absorption in our cell phones and Ipods and Iphones is likely to take us)—only time will tell. However, it may be a trend well worth watching in the years to come.